A Hungarian border fence built to stop migration flows, threatening the future integrity of Schengen. A founding member of the European Union, until very recently in the hands of far-right nationalists. A Mediterranean graveyard of 18,989 migrants who’ve drowned attempting to cross since 2014.

Facts don’t lie: more than poor, Europe’s handling of the migration crisis has been outright catastrophic.

Italy is always on the forefront whenever talking about the European migration crisis which started in 2014, both regarding the mass numbers of immigrants arriving at their shores and their controversial migration policies. Matteo Salvini is an unavoidable figure, steering Italy’s course on migration for over a year. It’s easy to point the finger at Salvini’s arguably inhumane practices. Nevertheless, Salvini is mostly a product, rather than the cause, of the lack of an effective European-wide response on migration.

With Salvini ousted from power in September, it’s important to reflect on his rise and migration policy, the real impact of immigration and what Europe can do to correct its past mistakes.

Salvini Ascending

Discontent towards Europe was undoubtedly a major driver to Salvini’s successful result in the 2018 general election. Migration, although pivotal to that discontent, isn’t alone in making Italians increasingly critical of Brussels.

Italy has faced a long period of stagnation since the beginning of the century, with real GDP per capita having decreased 3% since 2000, leaving Italy behind relatively to its European peers. The role of the single currency in this stagnation is debatable, but this period of low growth coincides with the introduction of the euro in 1999. Many Italians blame it for their stagnant economy and Salvini has often used this anti-euro sentiment to his benefit. His slogan for the 2014 European elections was ‘Basta Euro’ (‘No More Euro’), also campaigning against Brussel’s fiscal rules in 2018.

Italy has also faced en masse immigration, with a total of 656,040 migrants arriving to its shores since 2014. Simultaneously, anti-immigrant propaganda and fake news have swept the continent, fuelling hatred and mistrust towards foreigners. During the referendum campaign, Brexiteer Nigel Farage presented an anti-immigration billboard bearing a striking resemblance to a Nazi propaganda movie which described immigrants as ‘parasites undermining their host countries’ (Image1). In 2018, Orbán’s government sponsored a European-wide video, unfairly correlating refugees with the terrorist attacks across Europe. Even today, Ursula von der Leyen’s controversial choice to name the migration portfolio ‘Protecting our European way of life’ isn’t helping in preventing Europeans from regarding migrants as a threat.

Image 1: Nigel Farage presenting his anti-immigration billboard (left) and Nazi propaganda movie (right)

The impact of this xenophobic rhetoric is difficult to measure. Coincidentally or not, however, the regions with a higher percentage of immigrant population were the ones where Salvini gained most support in 2018.

The European Union, nonetheless, isn’t without blame in turning Italians against immigrants. Its current legislation on migration and asylum, the Dublin Regulation, defines that the first Member-State to which an asylum seeker arrives is solely responsible for their asylum application, giving all other Member-States the right to deport a refugee back to their EU country of arrival. Consequently, this places an unfair burden on border countries such as Italy, even though countries such as Germany receive more asylum applications. This has caused 24,000 deportations back to Italy from other EU countries between 2013 and 2018. Despite the EU recognising this as a major flaw, the reform of Dublin has been stuck in the Council since the crisis started, where the Visegrád Group (Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia) are blocking any reform which involves mandatory relocation quotas, refusing to host any refugees. The lack of a common European stance on migration left Italy with the full burden of dealing with this issue.

This sent Italians a clear message: if they were the ones responsible for all refugees arriving at their shores, they would no longer allow refugees to land. The path was open for someone with a hard stance on migration to step in.

Salvini Takes Action

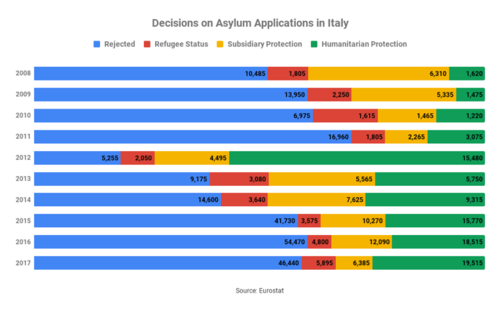

Salvini took office as Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister in June 2018 and his impact on Italy’s migration policy was highly noticeable. He quickly announced the closure of Italian ports to migrant vessels. 44,260 asylum requests were rejected. He shut an asylum centre in Sicily, one of the largest in Europe. He announced fines reaching €50,000 to rescue ships entering Italian waters. In September 2018, the Italian government approved the ‘Salvini Decree’ which, among other measures, removed the possibility of asylum applications being granted for ‘humanitarian protection’, which has been in recent years the most granted asylum type. This would greatly increase the number of rejected asylum applications and an estimated 670,000 immigrants would be living irregularly in Italy, essentially giving the Italian government the right to repatriate them.

Dismistifying Immigrants

But are Italians and other Europeans right to fear the ‘invasion’ of immigrants? Public perception of immigrants often doesn’t correspond to reality. For instance, despite the sharp fall of 80% of immigrant arrivals by sea to Italy between 2017 and 2018 (partially due to Salvini’s measures), studies show that 51% of Italians still think this number is not decreasing. Moreover, an average Italian thinks that 26% of the country’s population is foreign, while the true figure is 9.5%.

It is also vital to distinguish between a regular immigrant and a refugee. A refugee is fleeing rather than voluntarily moving. These words are often used interchangeably but, in 2016, only 34% immigrants arrived to Italy due to humanitarian crises, while the others deslocated to Italy either for family reunification (45.1% of cases) or to look for better life conditions and employment.

Immigrants common desire for social mobility might explain their higher rate of entrepreneurship when compared to national residents in many European countries (although no data is available for Italy, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor estimates this rate to be 12.5% for immigrants and 8.6% for national residents in the UK, 2017).

However, this is not the only way in which immigrants contribute towards their host country’s economy. An aging Europe desperately craves for rejuvenated workforce to sustain its social welfare systems, which are being stretched to their limits. Due to their younger age, in Italy, in 2008, 73.3% of immigrants belonged to the working-age population, compared to only 62.3% of Italians. Consequently, despite in the short-run receiving more in social benefits than they contribute with taxes, in the long-run their net contributions are positive, since they have a long working life ahead of them. In 2014, taxes paid by immigrant workers bore the cost of 600,000 pensions.

Studies also show that immigrants ultimately benefit the economy, decreasing unemployment and raising GDP per capita. While this verified in Italy since mass immigration began, it’s hard to quantify their contribution towards this, since it coincides with a period of overall economic recovery in Europe.

On the other hand, less than 15% of non-EU immigrants in Italy have tertiary education. This results in more than 70% of them being employed as low-wage manual workers, which can cause salary degradation and competition with underqualified national workers, which often causes social tensions and feelings of resentment against immigrants.

Another preconceived idea is that refugees don’t make an effort to adapt to local culture and language. However, a 2014 study shows that 60% of refugees living in Italy had an advanced knowledge of Italian.

Second Chance

The ousting of Salvini presents a chance for Europe to show Italians it can smoothly integrate, absorb and redistribute immigrants in a better fashion than displayed so far.

A quick reform of the ineffective Dublin Regulation is desperately needed. This, however, will be difficult as the Visegrád group remains reluctant in accepting mandatory relocation quotas. A temporary solution is being discussed. Germany and France would each automatically accept 25% of arriving immigrants, with Italy only keeping 10% to compensate for recent years. Other EU countries, including Portugal, are also available to join this scheme. In return, Italian premier Conte has agreed to reopen the ports.

Many EU politicians have also called for EU-funded asylum centres in North Africa and Middle East. This would reduce the number of war-fleeing refugees risking the life-threatening Mediterranean crossing and the migrant pressure on southern European countries. A reinforcement of FRONTEX, the European Border and Coast Guard, which is severely understaffed, is of paramount urgency to combat illegal human trafficking and reduce the number of drownings.

There’s also too much media depicting refugees as dangerous criminals which must be countered, namely by raising public awareness and sensitivity towards their desperate situation. This has proven effective in the past, as is the case of the photograph of the dead Syrian infant found on the shore of western Turkey. When Aylan Kurdi’s picture became viral four years ago, the Swedish Red Cross saw a ten-fold increase in recurring monthly donations to their fund for Syrian refugees.

Despite overcoming the peak of the immigration crisis, Europe still needs to find a way to deal with this issue properly. Only a strong demonstration of solidarity and cooperation will prove to Italy that there’s no need for them to elect an ultra-nationalist again. Europe has been given a second chance to show it can do better. There might not be a third.

Hi there! This post could not be written any better!

Reading through this post reminds me of my old

room mate! He always kept chatting about this.

I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good

read. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know a

lot about this, like you wrote the book in it or

something. I think that you could do with some pics to drive the message home a little bit, but other than that, this is wonderful blog.

A fantastic read. I will definitely be back.

LikeLike

Very nice write-up. I definitely appreciate this website.

Keep it up!

LikeLike

That is a very good tip particularly to those new to the blogosphere.

Simple but very precise info… Thank you for sharing this one.

A must read article!

Here is my site – consumers

LikeLike

Good day! I simply want to offer you a huge thumbs

up for the excellent information you have right here on this

post. I’ll be coming back to your web site for more soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person