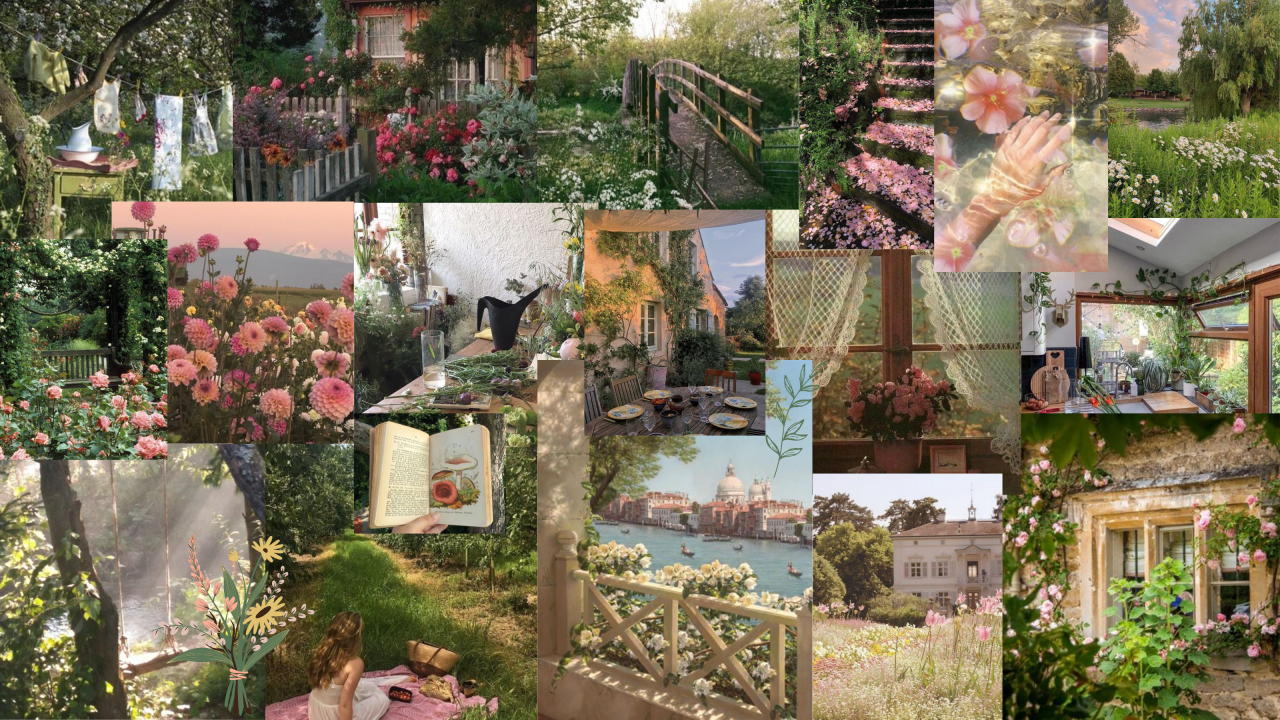

Picture the following scenario: Your student self walks into campus for yet another day of lectures and tutorials and notices that the surroundings are composed of living embodiments of a multitude of famous aesthetics. The “clean girl” passes by you on the way to the library. In class, a vision of pastel perfection and floral patterns, reminiscent of cottage core’s effortlessly soft look sits next to you. On the way home, someone exudes the quintessential “thrifted” look, adorned head-to-toe in vintage core goods.

It is, in fact, a visual treat, and, as you fight back the urge to hit the “checkout” button on your meticulously curated shopping cart, composed of items from the various aesthetics that captivated you today, you stop to think: Where do I fit in?

Core Aesthetics: How did they come to be?

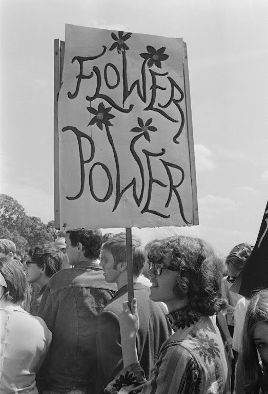

The rise of core aesthetics in the digital age is closely related to the decline of traditional subcultures. Subcultures, as defined by the Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, are an ethnic, regional, economic, or social group exhibiting characteristic patterns of behavior sufficient to distinguish it from others within an embracing culture or society. These often emerged organically among people with shared interests in music, art, literature, and political views. Examples of such are the 60s Hippies and the 90s Emo and Grunge subcultures.

As they grew and became more mainstream, subcultures fell victim to oversimplification, thereby allowing companies to benefit from their universally recognizable elements. For instance, the punk subculture, known for its rebellious nature and incorporation of leather jackets and ripped jeans, has greatly influenced fashion and how it is perceived by young adults nowadays who can buy the individual elements without necessarily subscribing to the movement’s original values and ideologies.

Recently, however, there has been progressively less presence of these subcultures in modern society. As Peter Watts notes in Apollo Magazine (2017): “There is a sense that this ties in with the rise of the internet, with a more interconnected society removing that need for intensely localized scenes, which often coalesced around a single record or clothes shop or particular club or band. The wide availability of music allows young people to explore sounds across genres and timeframes which could also disrupt that need for a tribal identity.”.

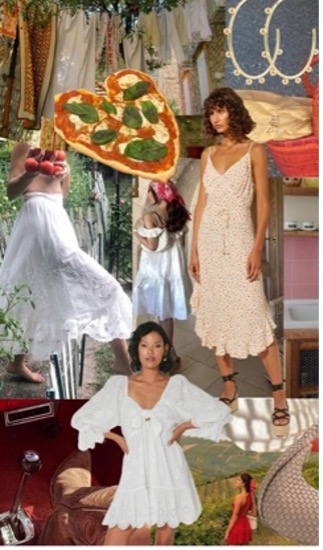

This decline has given space for the birth of “online core aesthetics”. Unlike subcultures, these aesthetics lack the sense of community that characterizes subcultures, since its followers often lack uniform musical tastes, political ideologies, or even physical places to meet up. Additionally, core aesthetics are associated with young people and the need to belong to a specific group with defining features, hence the suffix “core”. This newfound trend, mainly unsuccessfully, attempts to mirror the organic evolution of subcultures but with a more digital and global approach. Even so, many of these aesthetics, such as the “tomato girl” or “mermaid core”, are introduced to the public, through magazine fashion articles and social media, while still in development, coalescing with companies whose primary goal is profit. By the end of one of the thousand articles on a new trend, there is a segment which relates to “how to dress like” such trend or aesthetic, incentivizing readers to buy the listed products. This, then, becomes a question of what comes first: The core aesthetic or the news article about such?

Core Aesthetics and Consumerism

In the past decades, people would resort to celebrities, models, and fashion magazines to set trends. As this group of institutions was narrow and not easily accessed, exposure to potential new trends was rather limited, keeping fashion cycles slower and almost effortless to control.

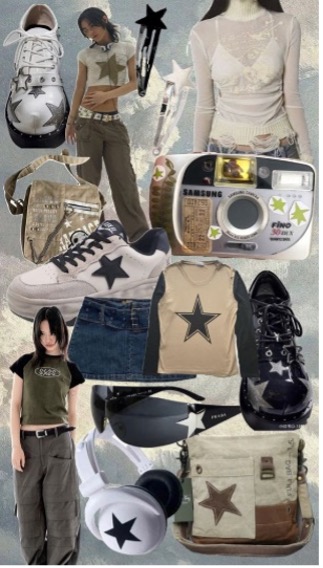

The rise of the internet has clearly accelerated products’ life cycle in the market and the evolution of core aesthetics. Online communities and media platforms provide the means for people to explore and express their different interpretations on fashion trends, while algorithms fragment online communities into taste-specific groups, eroding the notion of a universal mainstream, when, in reality, different individuals consume different “mainstream content”. This results in culture becoming less a focal point in young people’s identity, but rather the yearning to belong to an existing group.

Social media platforms such as Instagram, TikTok and Pinterest also serve as a stage for e-commerce and trust-based marketing, which, more often than not, breaks the consumerism dilemma into a simple choice for consumers. One example is that of Addison Rae, a TikTok content creator who, upon launching her makeup line, ITEM, initiated a trend by applying lip gloss, a product associated with the Y2K aesthetic, while holding her phone, showcasing her product. This ordinary trend propelled Rae’s net worth to 15 million dollars in 2022, since young girls who are still figuring their identity are pushed toward consuming the current trends to conform to a certain type of girl: clean girl, tomato girl, strawberry girl, and so on.

Along with core aesthetics, come micro trends which regard specific items in an aesthetic or fashion trend that become rapidly popular, while fading into the background rather fast as well. These fuel a lot of the consumerism patterns seen nowadays, since they are easily disposable as one’s primary closet pieces and usually incorporated in fast fashion catalogs, lasting but one season. Some examples are the House of Sunny’s hockey dress, patchwork jeans, and, more recently, the blueberry pink nails trends.

It is important to note that micro trends usually stem from small and sustainable brands, but uncontrollably expand into a fast fashion item that no one would wear within months, thereby not attributing brand recognition to the original designer.

Aftermath of the current overconsumption

Many aesthetics and trends rely on the romanticization of everyday life and self-care activities. Despite modern society’s awareness around overconsumption and its environmental impact, the pursuit of the perfect lifestyle through specific aesthetics is still a prevalent issue. In 2018, the recorded units of rigid plastic created for the beauty and personal care industry, which is greatly fomented by trends and aesthetics, amounted to 7.9 billion in the U.S alone. Most of the used plastic for packaging is not recyclable, yet still consumed around the world with 90% being mindlessly thrown away.

In the clothing industry, brands such as Shein, Zara, and H&M play a significant role in consumerism and the incorporation of core aesthetic items in people’s monthly or even weekly consumption of goods. In an environmental viewpoint, the overconsumption, and thereby, excessive manufacturing of clothing items represents 2 to 8% of annual greenhouse gas emissions, more than all international flights and marine shipping combined.

The aftermath of the mindless adoption of core aesthetics includes, along with environmental issues, the discarded clothing in landfills is set to amount to 134 million tons of material by the end of the decade.

Final Thoughts

It has become quite intuitive that social media, core aesthetics and consumerism are intertwined. However, aesthetics is not the sole motivator of overconsumption as, continuously, micro trends emerge and promote unnecessary consumption of goods with short-lived cycles within the fashion industry. It must be noted that not all aesthetics fall into consumeristic behaviors, as dark academia or cottage core already have a rich community base that is mostly detached from just overspending.

Sources: Statista, Vogue, Merriam-Webster, The New Yorker, Earth Day, Earth.Org, Apollo, Weller, Wivian. “The Feminine Presence in Youth Subcultures: the Art of Becoming Visible”. 2006. In http://socialsciences.scielo.org/

Madalena Zarco