Miracles do not only arise in nature but can also be witnessed in economic contexts. Similarly, they evoke fascination and amazement, however, experiencing wonders can also heighten awareness of their fragility and develop a stronger sense of responsibility, making it even more thrilling to analyze their origins, synergies and lessons.

The “Miracle on the Han River” describes South Korea’s economic transformation from one of the poorest nations in the world to a global industrial and economic powerhouse within a few decades. Following the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, South Korea faced immense challenges, containing widespread poverty, devastated infrastructure, and reliance on foreign aid, primarily from the United States. Its gross national product (GNP) per capita in 1962 made up barely $87, reflecting its fatal economic state.

However, beginning in the 1960s, South Korea started a journey of rapid industrialization and economic development – a transformation being so significant and unparalleled that it was characterized as the “Miracle on the Han River.” The latter arised and simultaneously indicated how a nation, through visionary leadership, economic planning, and societal mobilization, can overcome substantial challenges and achieve sustained growth. Today, South Korea serves as a model for developing nations aiming to replicate its success.

Background

South Korea’s economic transformation was initiated under the leadership of President Park Chung-hee in the 1960s. His government adopted a developmental state model that prioritized economic growth through export-oriented industrialization and infrastructure development. This approach included significant government intervention, incentives for private sector growth, and a focus on creating global competitiveness.

Park aimed to make South Korea self-reliant and less dependent on foreign aid, especially from the United States, while also competing with North Korea’s growing industries. For him, economic growth was not just about improving the economy but also about building national security and pride.

Though his leadership was authoritarian and often criticized for limiting human rights, Park played a key role in South Korea’s economic progress. His idea of “treating employees like family” helped increase productivity among workers.

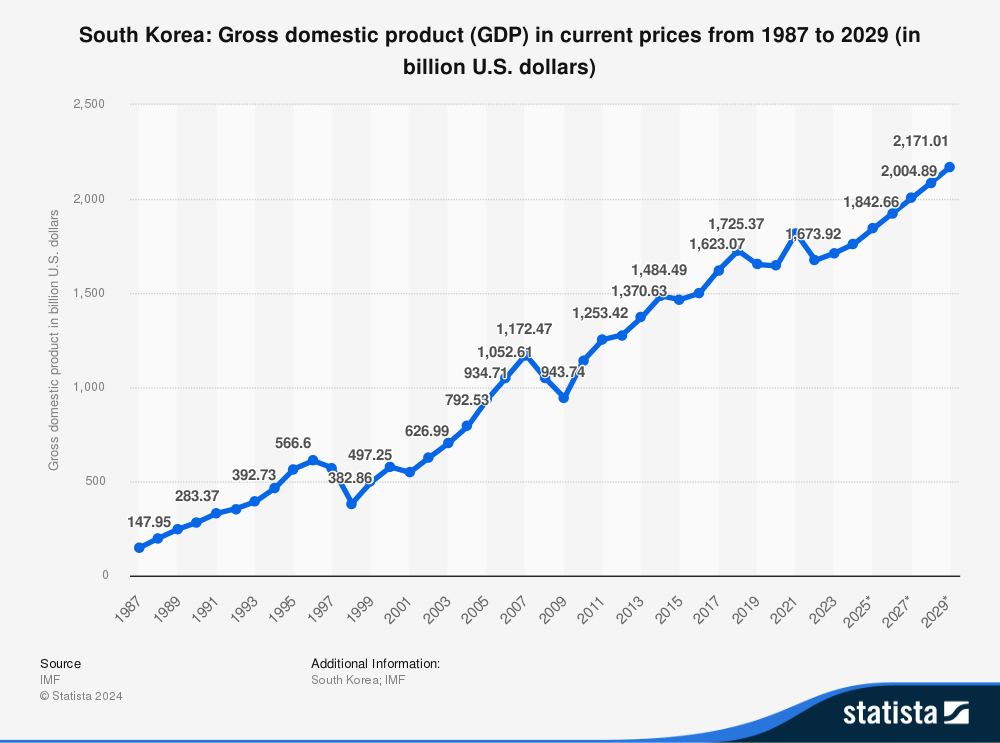

A key element of the economic transformation was the establishment of Five-Year Economic Development Plans, which outlined ambitious goals and focused resources on priority sectors. The state also invested heavily in education and technology, creating a skilled workforce capable of supporting industrial growth. As a result, South Korea experienced an average annual GDP growth rate of over 7% for several decades, becoming one of the world’s largest economies by the late 20th century.

The chaebŏls has a key to success

After 1961, the South Korean government worked closely with business leaders to achieve its development goals. These businesses, known as chaebols, were family-run corporate groups that exercise monopolistic or oligopolistic control over certain products and industries.

The chaebols received various advantages, such as reduced import duties on capital goods and lower rates for utilities. The state closely monitored the chaebols to ensure they used government support effectively. If a chaebol failed to meet economic targets or compete in local and global markets, it risked losing state support.

The chaebol system proved highly successful, with the top ten conglomerates growing at more than three times the rate of the country’s GDP. Among these conglomerates we find our todays Samsung, LG, and Hyundai.

The change in the 70s

As the United States became less reliable as a military and political ally, particularly after establishing relations with the People’s Republic of China, South Korea felt an increased urgency to become autonomous. This included manufacturing its own weapons, producing capital goods, and competing with North Korea’s advancements in heavy industry.

To address this, South Korea shifted its focus to heavy industry and capital goods production while increasing restrictions on foreign direct investment.

Although many foreign experts doubted South Korea’s ability to sustain a heavy industrial base due to its size and level of development, the plan succeeded. The economy grew at double-digit rates even during the challenging global conditions of the 1970s. Industries like steel and shipbuilding grow. Steel production increased and by the 1980s, South Korea had become the world’s second-largest shipbuilder, known for completing orders quickly and reliably.

From Military Leadership to Democratization

On October 26, 1979, President Park Chung Hee was assassinated. After this, Chun Doo Hwan, a military leader, became president and ruled from 1980 to 1988. He continued many of Park’s economic policies, but during the 1980s and 1990s, South Korea’s economy started to change. Exports shifted to more advanced products, such as consumer electronics, computers, and semiconductors, while textiles became less important. Industries became more focused on machines and technology rather than human labor.

In 1987, South Korea began to democratize, which affected economic development. The days of strong, authoritarian governments ended, and a politically active middle class and stronger labor unions started to influence policies. Wages increased quickly during the late 1980s and early 1990s, partly because labor unions had gained more power.

After 1996

In 1996, South Korea joined the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a group of 30 developed nations. This marked South Korea’s transition from a developing country to being recognized as a wealthy, developed nation. However, the country still faced challenges. South Koreans worked some of the longest hours among OECD countries, and the quality of life was not yet equal to other developed nations.

In 1997, the Asian financial crisis struck, exposing serious problems in the economy. Corporate debt had grown to dangerous levels, leading to the need for an international rescue package. To recover, South Korea forced large business groups, called chaebǒls, to focus on their main businesses and reduce their debts. The government also introduced reforms to make the labor market more flexible. These efforts paid off, with the economy experiencing rapid growth in 1999–2000. South Korea went from being a debtor nation to a creditor nation within a few years.

By 2017, South Korea was known globally for its technological innovation. Its GDP per capita had risen slightly above the European Union average, and the country ranked among the best in the world for health standards and education.

Challenges

Despite these successes, the Miracle on the Han River also came with challenges. Rapid industrialization intensified income inequality and environmental degradation.

While South Korea became a major exporter of entertainment, other parts of its service economy failed behind. The dominance of chaebǒls also created problems for smaller startups, limiting their growth and influence. These large corporations held significant power over public policy, raising concerns about fairness in the economy.

Additionally, South Korea faced demographic and environmental challenges. It had one of the lowest birth rates in the world and a population that was living longer than ever, which put pressure on social systems. There were also significant issues with air and water pollution, as well as other environmental costs of rapid development. These challenges reflected South Korea’s transition into a prosperous and technologically advanced country by the 21st century.

Conclusion

The “Miracle on the Han River” demonstrates how visionary leadership, strategic planning, and societal mobilization can transform a nation from the brink of collapse into a global economic powerhouse. South Korea’s journey from post-war devastation to technological and industrial excellence offers valuable lessons for developing nations striving for similar growth.

However, this remarkable success came with significant challenges. Rapid industrialization aggravated income inequality, environmental degradation, and demographic pressures. The dominance of chaebŏls, while instrumental in driving growth, prevented innovation from smaller startups and raised concerns about economic fairness.

Drawing a bigger picture, South Korea’s story is not just about growth but also about resilience and adaptation. From overcoming financial crises to transitioning into a democratic society, South Korea has shown the importance of evolving in response to opportunities as well as challenges. Since the country continues to address issues like an aging population and environmental sustainability, it demonstrates a testament of the power of determination and strategic vision for shaping the destiny of a nation.

Sources: Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences; Asian Affairs: An American Review; Situations; International Journal of Multimedia and Ubiquitous Engineering.

Beatriz Gomes

Mara Blanz