Last month, the entire Iberian Peninsula experienced a surreal moment: a day without electricity, cut off from the rest of the world. Videos of the blackout quickly made the rounds online—many lighthearted and humorous—showing people taking to the streets, enjoying the unexpected break from technology, and drinking beers before the refrigerators got warm.

But the event also sparked widespread speculation about its cause, which still remains uncertain. Among the many theories—though unconfirmed—one pointed to a largely overlooked issue: not the energy transition itself, but a specific and often neglected aspect of it—the non-dispatchability of renewable energy sources, and the challenges this creates for the entire energy market.

Renewables and energy price volatility

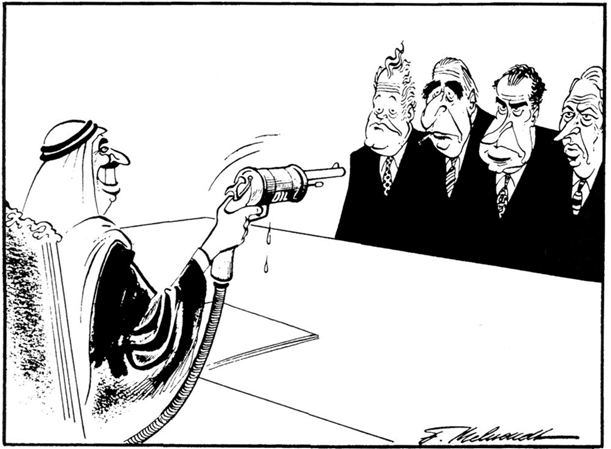

Renewable energy sources offer more than just an environmentally friendly alternative to fossil fuels. They also have the potential to enhance price stability in the electricity market. While fossil fuels are exposed to the volatility of international markets—often affected by geopolitical tensions, conflicts, or supply disruptions (such as the OPEC oil crises or the recent cuts in Russian gas exports)—renewables are locally produced and less susceptible to these external shocks.

By diversifying the energy mix and reducing reliance on any single energy source, renewables help lower wholesale electricity prices, as shown by Cevik and Ninomiya (2023). But the benefits go beyond price levels: the increasing share of renewables in electricity production also reduces overall price volatility. In particular, it limits the extent to which spikes in fossil fuel prices—like those caused by sudden shortages or political tensions—can affect the broader energy market. This makes energy systems not only greener, but also more resilient and economically stable (Forrest and MacGill, 2013).

The Role of Wind and Solar in Price Volatility

Not all renewable energy sources are equal when it comes to price stability. It’s important to distinguish between dispatchable renewables—those whose output can be controlled, like hydroelectric power—and non-dispatchable or intermittent sources, such as wind and solar. To illustrate this, imagine a hydroelectric plant versus a wind farm. In a hydro plant, operators can regulate electricity production by controlling water flow. While it’s not completely immune to weather patterns, its output is largely predictable and controllable.

Wind and solar energy, on the other hand, depend on weather conditions that are neither constant nor controllable. While forecasting technologies have improved, operators still cannot control when the wind blows or the sun shines. This unpredictability introduces greater volatility into the electricity market.

Mohan et al. (2020) describe a phenomenon known as the “volatility cliff.” As the share of intermittent renewables increases, price volatility tends to rise. But beyond a certain threshold—what they call the cliff—this volatility can accelerate dramatically, leading to severe price swings and instability in electricity markets. This highlights the need to consider not just how much renewable energy we produce, but also what types and how they are integrated into the energy system.

Figure 1 – Germsolar Thermasolar Plant in Andalusia, source Westend61

Some Data on Spain and Portugal

Looking at the Iberian Peninsula, Spain and Portugal form what is often referred to as an “energy island,” with relatively limited electrical interconnection to the rest of Europe. In 2024, wind and solar accounted for nearly 50% of the electricity mix in both countries, while renewables overall exceeded 60%. This is undoubtedly a significant achievement and a source of pride for the Iberian nations. However, such a high share of intermittent renewables also brings challenges.

The first issue, as mentioned earlier, is volatility. Just two days after the well-known blackout, on April 30th, Spain’s electricity price jumped from €5.79/MWh to €31.83/MWh in a single day. Although Spanish prices have experienced sharper fluctuations in absolute terms in the past, this still represents an increase of over 450%—a reminder of the market’s sensitivity.

The second issue is the mismatch between energy supply and demand, a challenge that is becoming more frequent with the growth of intermittent renewables. In 2024, Spain recorded 247 hours of negative electricity prices; Portugal, 196. Negative prices mean that producers are willing to pay to offload excess electricity they cannot store or use. As the share of wind and solar continues to rise, such episodes are likely to become more common.

While this may seem like good news for consumers, in reality, it poses a serious problem for energy producers and investors. Uncertainty in revenues and the risk of selling electricity at a loss can deter investments in new renewable projects, paradoxically slowing down the green transition and the path toward decarbonization.

Figure 2 – Energy Mix of Spain and Portugal, elaboration from Ember

The Challenges

These reflections lead us to consider the broader challenges that renewable energy brings to the energy sector—challenges that call for systemic reforms and improvements.

First and foremost, as the share of renewables in the energy mix increases, it is crucial to simultaneously invest in energy storage technologies and grid-scale storage systems. These systems can help absorb excess electricity during periods of high renewable production and release it when production drops, directly addressing the problem of intermittency. However, such infrastructure is still expensive and complex to implement on a large scale.

Second, a more integrated and interconnected European electricity grid is necessary. Enhanced cross-border interconnections would allow surplus energy from one country to be exported to another where it is needed, making the overall system more efficient, resilient, and less prone to localized imbalances.

Third, we need to rethink and update the regulation of electricity market bidding systems. Current rules were designed for a fossil-fuel-dominated system and are increasingly unfit for a market where the marginal cost of renewable generation is often close to zero. Without reform, the current pricing mechanisms could undermine the profitability and long-term sustainability of renewable investments.

The Delicate Balance of Decarbonization

The challenge of decarbonization is a delicate one. A massive investment in renewable energy is not, in itself, a silver bullet—and, paradoxically, it can even become counterproductive if not accompanied by a broader reform of the entire energy system. A successful energy transition is not just about installing more solar panels or wind turbines; it’s about designing a system in which these technologies can function efficiently, sustainably, and reliably over time.

The success of any well-intentioned initiative depends not only on its technical merits but also on its ability to remain attractive and sustainable over time. For renewable energy to remain appealing—not only to consumers but also to investors—it must offer price reductions, price stability, and long-term reliability. Maintaining this attractiveness requires thoughtful policy design, targeted incentives, and a regulatory framework that keeps pace with technological evolution and market dynamics.

Sources: Aurora Energy Research, El Economista, Ember, Financial Times, …

Veronica Guerra

Editor and Writer