Inflation has been making headlines all around the globe, as prices increase at unprecedent rates. But how is inflation measured? Are the measures presented by policy makers trustworthy?

Inflation has always been a hot topic of discussion – and a particular favourite of central banks all over the world. Indeed, with price stability as one of the core objectives of virtually all central banks across the globe, it comes as no surprise that inflation targeting is seen as the key guiding point for monetary policy.

So, if inflation is such a key determinant of economic activity in the eyes of most central banks, how do they go about measuring it? Multiple measures are generally and simultaneously used, with the most common being undoubtedly the CPI (Consumer Price Index) – used for example by the FED in the US – as well as its EU counterpart, the HICP (Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices), favoured by the ECB.

One may ask to what extent are all these measures able to fully capture the actual inflation that is being felt in the economy, and what role do central banks play in assessing inflation and its respective expectations, seeing as the ultimate decision of when and how to act when it comes to inflation targeting falls entirely upon them.

Measuring Inflation – From the CPI to more complex metrics

Most Central Banks stated primary objective is to maintain price stability. In the Euro Area and in the U.S., the European Central Bank and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve normally have their eyes set on a long-run target of 2% annual inflation. For Central Banks to keep track of the effect that their monetary policy is having on current inflation they need measures of… well, inflation[1]! Unfortunately, there is not one which is truly accurate or one which could take everything into account, and commonly used measures, such as the CPI (Consumer Price Index), are regularly subject to criticism of their methodologies and their over or under-estimation of inflation, depending on when and who you ask.

The CPI is one of the most mentioned measures of inflation and, generally, consists of, at a first stage, obtaining a set of weights to give to different expenditure items based on the consumption pattern of the average consumer (In the U.S., the U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics, which publishes the CPI, calculates this based on its Consumption Expenditure Survey). Next, in the case of the U.S., for example, the U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics obtains data on the prices of over 90,000 goods. Based on the previous weights, the index is then calculated and with it, we should get an idea of how the price of the average consumer’s basket of goods has changed.

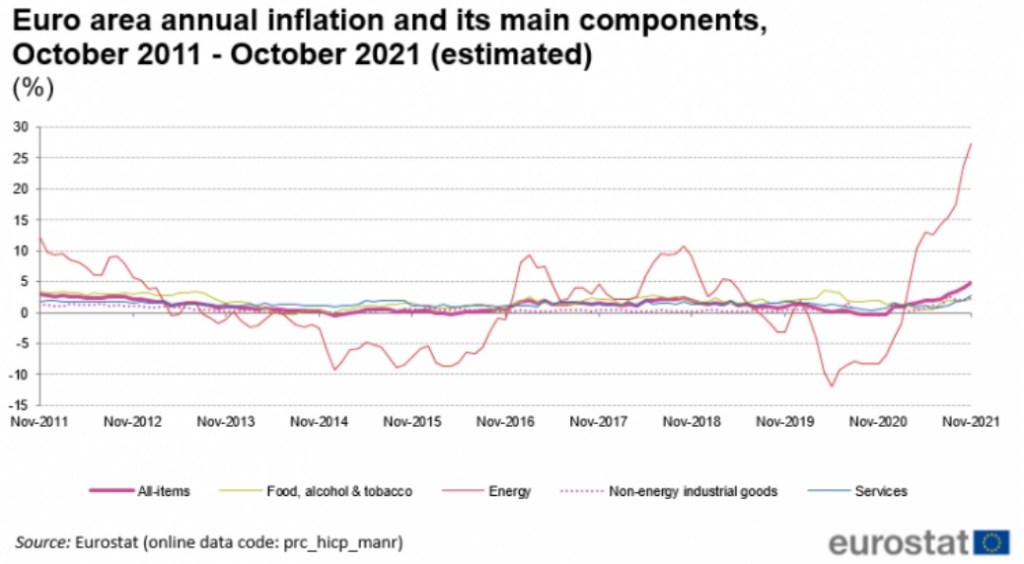

However, there are many pitfalls associated with its interpretation, especially in the context of informing monetary policy. For example, a considerable percentage of consumers’ income is spent on energy consumption. As has become quite apparent recently, these commodities are subject to wild price fluctuations. However, despite being largely caused by factors other than the monetary policy of Central Banks, the recent price increase in energy has reflected strongly on the CPI. To combat this, we may remove energy and food (which may also be quite volatile) items from the CPI and present only the Core CPI.

And we may go even further and say that, in fact, the Core CPI may still be providing a biased estimate of inflation due to large changes in specific items and that, instead, we should look at the Trimmed CPI, which has the top 8% and bottom 8% biggest price increases and decreases chopped off. Others may say that we should look also at the Median CPI which measures the price change of the 50th percentile good on the basket list.

Taking all these different measures into account we can build a better, more complete picture of whether recent inflation measured by headline CPI in the U.S. is simply related to wild swings of a few items due to supply shocks, or whether it is a broad-based, demand-driven phenomenon resulting from expansionary monetary policy.

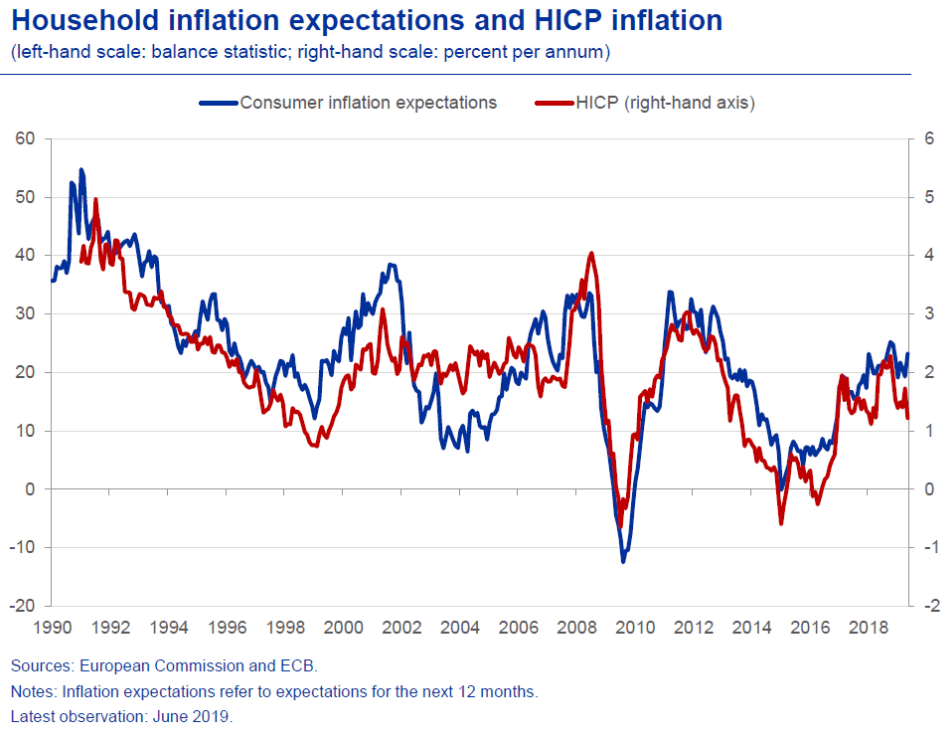

Beyond the usual metrics – The importance of Inflation Expectations

The focus of Central Banks to meet their inflation targets is highly correlated with inflation expectations. These are simply the rate at which people expect prices to rise in the future. They matter because actual inflation depends, in part, on what we expect it to be. Let’s say that everyone expects prices to rise at a 4% rate over the next year; then, businesses will want to raise prices by at least that amount, and so will want workers to increase their wages. All else equal, if inflation expectations rise by one percentage point, actual inflation will tend to rise by one percentage point as well.

This means that for Central Banks it is important to anchor expectations at their inflation targets. The absence of anchoring, in a period of high inflation, can create a wage-price spiral. This term defines the cause-and-effect relationship between rising wages and rising prices. The wage-price spiral suggests that rising wages increase the demand for goods and cause prices to rise. These price rises will then increase the demand for higher wages and the cycle repeats.

Conclusion

Most of the younger European generations have never experienced high inflation. Still, the inflation rate was not always stable and low. In the ’70s, with deregulation of the international monetary system and two oil shocks, inflation had climbed to values never seen before (around 12% – 13%) only declining in the next decade (80’s). With some fluctuations over the years, this measure has seen a downward trend over the years laying down values between 0.18% in 2016, 1.7% in 2018 and 0.5% in 2020.

This trend can be changing. In the past months, inflation has been alarmingly increasing, now reaching values that are further away from the usual target, with the EU currently registering around 3.6% inflation rate and the US a concerning 5.4%.

The fact that inflation is rising is not entirely unexpected, as expansionary monetary policies such as the ones that have been conducted for the past year and a half as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic – characterized by massive bond-buying initiatives that provide ample injections of liquidity in the economy and incredibly low interest rates – are usually followed sooner or later by a rise in inflation as demand starts to pick up once again. Coupled with this, the skyrocketing energy prices that come as a natural response to the global energy crisis that we are currently facing have also contributed to pushing this raise in prices even higher.

Nevertheless, even though the inflation values that exclude these energy fluctuations are a bit more promising (EU = 1.8% and US = 4%), they are still off from the recommended ones (especially the US), which indicates that a Central Bank intervention should be imminent, particularly from the FED where the scenario appears to be worse. Still, Central Banks are in-between the sword and the wall. On one side we see rising inflation pressure but, on the other side, there is still an economy that is recovering from the impacts of the pandemic crisis. Nonetheless, it is clear that the current landscape would not be sustainable for long, so it could be said that the Central Banks’ reluctance to act upon it will inevitably have to come to an end in the near future.

[1] Central Banks also often look at measures of inflation expectations to guide their monetary policy.

Sources: EBC, Investopedia, IMF, Trading Economics

Diogo Almeida

João Baptista

Inês Lindoso

João Correia

Well I definitely appreciated reading through it. This

topic made available from you is quite positive for

right planning.

LikeLike