A look into the integration and competition concerns of the Draghi Report

“Europe faces a choice between exit, paralysis, or integration” – Mario Draghi

Unlike many of us perceive, European integration is far from figured out.

In practical terms, integration is all-around. From the euro to the European Court of Justice, touching on more simplistic aspects such as the citizen’s identification as Europeans. On the other hand, macro shocks like the Sovereign Debt Crisis might be able unveil more sensitive aspects of this fragile social, economic and political commitment, for example, by leading us to question whether European countries should pay for each other’s debt.

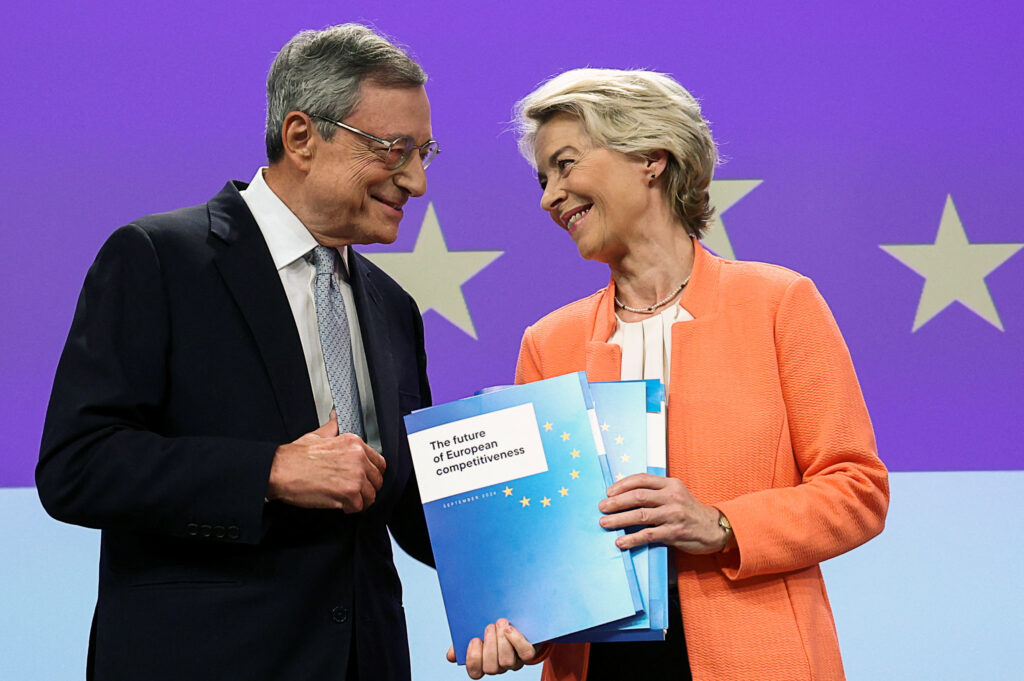

So, how much integration is too much integration? Mario Draghi, former Italian prime minister and president of the European Central Bank (ECB) brings this issue back to the fore with the release of his 400-page report on European competitiveness. There, Draghi identifies a rather plain and apparently sensible solution for its stagnation: cooperation and coordination. The former president of the ECB calls for an additional annual €800bn in investment, paired with a profound policy redesign to foster the European’s assertiveness in global competition. For many, a courageous punch full of truth, while for others, a political disaster.

This article will further delve into the specific intricacies of the mediatic Draghi’s Report, while dissecting the competition dilemma that Europe faces and intertwining them with the pervasive message of integration throughout report. Thus, alluding to the question of whether it exists a trade-off between resilience in global position and the core of current European values.

Background

The idea that the European Union is falling behind the United States, China and other advanced economies, when it comes to competitive edge, has been abiding for a while now.

The report dedicates a fair number of pages exploring the evolution of these dynamics. For instance, the gap in GDP level at constant prices is said to be widening, from 15% in 2002 to 30% in 2023. When measured in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), it amounts to 12%. The gap growth is more sluggish when translated into per capita terms, but the authors claim is still significant, rising from 31% in 2002 to 34% today. The catalyzers for these disparities are precisely differentials in productivity: About 70% of the gap in per capita GDP with US at PPP is explained by lower productivity levels in the EU.

On the other hand, the European Union is the proud face of some of the lowest levels of inequality, reportedly disclosing rates of income inequality around 10 percentage points below the ones evidenced in the United States (US) and China. It also surpasses these countries when it comes to life expectancy at birth, low levels of infant mortality, and education. In fact, its education systems allow a third of adults to have completed higher education. The EU is also the world leader in sustainability, environmental standards and progress towards the circular economy. (2024, The future of European competitiveness – Part A).

Plans had already been forged to deal with this issue of modest competition efforts across the European landscape. In November 2023, Ursula von der Leyen delivered her annual State of the Union speech, where she presented the main lines of action for the European Commission for the next year. Von der Leyen dedicated around a third of her speech to reshaping the EU’s economy, but the headline announcement was, precisely, Draghi’s Report. (2023 Foy)

Proposals

The report identified three main areas of action: The first is closing the innovation gap with America. According to the report, emerging technologies are still underdeveloped in the EU, not by lack of ideas or competence, but because of structural blocks, in the form of said inconsistent and restrictive regulations. Europe must focus on easier access for researchers when it comes to the commercialization of ideas, joint public investment in breakthrough technology or even investment in infrastructure to lower the cost of developing AI. Furthermore, training and adult learning should be at the core of the agenda.

The second area for action is combining decarbonization with competitiveness, by reforming Europe’s energy market, so that end-users can benefit from a competitive clean energy price, supporting industries that allow for decarbonization (e.g. clean tech and electric vehicles), while jointly promoting green industries.

The third area is increasing security and reducing dependencies. This vector of action is a result of the political turmoil instituted by the geopolitical instability. The EU is called to build a true “foreign economic policy”, by establishing coordination mechanisms in trade agreements and direct investment, ensuring stock of specific critical goods and devising industrial partnerships to establish robust supply chains.

To add on to this, the article takes a more thorough look at some more specific recommendations that have been particularly featured within the mediatic space, as the ones where it may be more difficult to achieve political consensus towards.

Competition Policy

“There is a question about whether vigorous competition policy conflicts with European companies’ need for sufficient scale to compete with Chinese and American superstar companies” – Draghi’s Report

A controversial point of discussion encompasses the question of competition policy enforcement, particularly mergers. EU antitrust policy has long been praised for protecting against abuses of dominant position. However, the report claims that this might be compromising the forging of European world-beaters, instead of only preserving competition within the EU (2024, Financial Times). In practical terms, this can be translated into the concern that European firms won’t be able to compete with significant global firms.

To achieve this, the report suggests an increased weight of the innovation factor in the assessment of mergers, by allowing higher market share concentration if this were to produce the development of new technologies by the merging firms. Of course, this might raise concerns regarding the misuse of this type of defense on a merger deal, allowing for a situation in which firms might commit to innovation only for the possibility of acquiring increased market power. So, Draghi suggests making companies showcase measurable levels of investment that can be tracked in the years following merger approval. The commission might, for instance, require companies to provide data on pricing or investment.

What is more, it is proposed a less stiff approach towards collaboration between rival corporate executives, with the argument that coordination might be necessary to maximize investment in research, or technological standardization (2024, Foy & Espinoza).

The report also recommends defining telecoms markets at the EU level – as opposed to the Member State level. To exemplify, a merged telecoms group could function in an almost monopolistic setting in individual countries, if their market share across the entire single market was less than 40 percent, which serves as a threshold for merger policy (2024, Foy and Espinoza).

These last measures have been subject to much mediatic scrutiny. On a paper published in Vox EU, the professors Tomaso Duso, Massimo Motta, Martin Peitz and Tommaso Valletti expressed their concerns regarding the telecom policy recommendations provided by the report. They claim that “They propose a broader, EU-wide market definition, which would artificially de-concentrate the relevant market, thereby making intra-national mergers appear no longer problematic on paper”, which ultimately creates the possibility to accept mergers that would be detrimental to European businesses and consumers.

Integration

Draghi claimed that the new “industrial strategy for Europe” would cost approximately €750- €800bn, which corresponds to 4.4-4.7 percent of EU GDP. Large amounts of money should be placed on joint funding key projects, such as innovation, as well as other European “public goods” —such as defense procurement, cross-border grids or common energy infrastructure.

Another concern expressed in the report points to the levels of financial fragmentation of the capital markets of the EU. Its integration is seen as an essential procedure towards the introduction of economic momentum that would allow for the development of the investments needs.

With the case of banking fragmentation, the report reminds us of the incomplete implementation of the Banking Union. While the unified supervision aspect is solidified, Europe has failed to implement a common debt insurance scheme, and the single resolution authority lacks a financial backstop. One of the proposed actions to facilitate this process is the creation of a common safe asset, particularly, the report appeals to “issue common debt instruments to finance joint investment projects that will increase the EU’s competitiveness and security.” However, it also established that a necessary condition for this to happen would be that “the political and institutional conditions are in place”, which can signify an impediment.

Moreover, the report asks for the extension of qualified majority voting (QMV) in the Council of The European Union, such that voting subject to QMV would be elongated to more areas, or even generalized, implying the end, or at least, reduction of the veto power under unanimity voting.

The difficulty here lies exactly in gaining political momentum to implement such reforms. In fact, the German finance minister Christian Lindner has already spoken on the matter, dismissing the Draghi’s suggestion to raise additional common debt to fund breakthrough innovation: “Each individual EU member state must continue to bear responsibility for its own public finances”. (2024 Hall). Eelco Heinen, finance minister of the Netherlands, said that “Europe has to grow, and I totally agree with that. An economy will grow if you reform (…) more money is not always the solution.”.

Conclusion

To conclude, the Draghi Report could represent either a turning point for Europe or just another document to be archived and forgotten about in the years to come. And although it may not be translated into policy action, at least for the time being, it has the power to ignite the public discussion back to “After all, what is the Europe that we want?”

References: Dragui, Mario. 2024. “Mario Draghi outlines his plan to make Europe more competitive”. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2024/09/09/mario-draghi-outlines-his-plan-to-make-europe-more-competitive

Draghi, Mario. 2024. The future of European competitiveness: Part B | In-depth analysis and recommendations. European Comission. https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/ec1409c1-d4b4-4882-8bdd-3519f86bbb92_en?filename=The%20future%20of%20European%20competitiveness_%20In-depth%20analysis%20and%20recommendations_0.pdf

Draghi, Mario. 2024. The future of European competitiveness: Part A | A competitiveness strategy for Europe. European Comission. https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/97e481fd-2dc3-412d-be4c-f152a8232961_enfilename=The%20future%20of%20European%20competitiveness%20_%20A%20competitiveness%20strategy%20for%20Europe.pdf

Foy, Henry. 2024. “Why Draghi went for broke in calling for €800bn of new EU spending”. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/76e8458d-3eb7-46d3-8d9c-42d524d60800

The Editorial Board. 2024. Whatever it takes to boost European competitiveness”. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/a87af4c4-5e5f-44a8-88a5-9a4037a16d19

Foy, Henry and Ian Johnston. 2023. “The EU’s plan to regain its competitive edge”. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/124b4cdb-deb9-49a0-b28d-d97838606661

Foy, Henry, Javier Espinoza, and Paola Tamma. 2024. “Mario Draghi confronts the EU’s merger police”. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/515d5a42-a760-42f1-9afa-89d4dcdc2a99

Duso, Tomaso, Massimo Motta, Martin Peitz , and Tommaso Valletti. 2024. “Draghi is right on many issues, but he is wrong on telecoms”. Vox EU. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/draghi-right-many-issues-he-wrong-telecoms

Hall, Ben. 2024. “Will Mario Draghi’s masterplan get the momentum it needs?”. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/a5e1264c-4004-440e-b3d9-2e130a68853

Maria Francisca Pereira