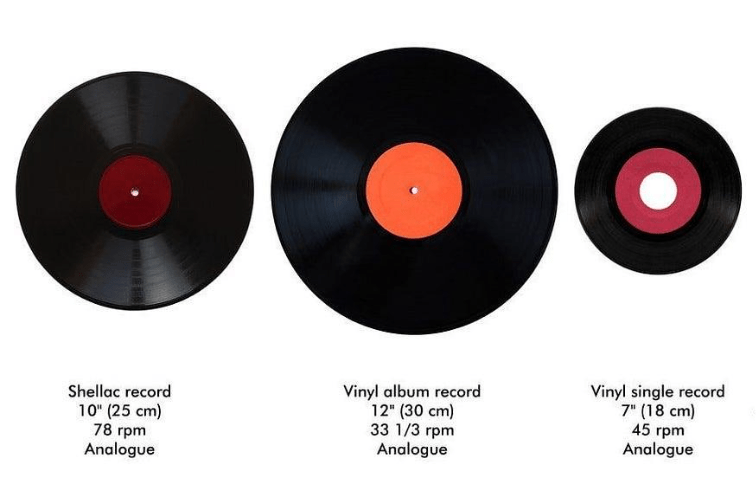

Before 33s, before 45s, and long before Spotify playlists, music moved at a speed most people today have never experienced: 78 revolutions per minute. These shellac discs weren’t just early records — they were time machines, cultural capsules, and experiments in sound. Place a needle on one, and you’re instantly connected to a world over a century old: jazz spilling out of a New Orleans club, blues echoing from a Mississippi porch, classical orchestras captured in studios that smelled of wood, varnish, and ambition.

Most music listeners today assume vinyl starts at 33 or 45 RPM. Few realize that for decades, 78s were the format that defined recorded music, shaping how songs were written, performed, and even how we perceive rhythm and melody. Though they were eventually replaced by longer-playing, more convenient formats, 78s left a legacy that still pulses in collectors’ crates, DJs’ loops, and archival vaults.

The Speed That Defined an Era

The story of 78 RPM begins with engineering necessity. In the early 20th century, phonographs were mechanical marvels, and shellac discs became their natural companion. Heavier and more brittle than modern vinyl, these discs required a rotational speed that balanced mechanical stability with audio fidelity. 78 revolutions per minute emerged as the practical standard.

In truth, “78” wasn’t always precise. Early records spun anywhere between 70 and 90 RPM depending on the manufacturer or motor. It took time, industrial consensus, and international standardization to settle on 78 as the global norm.

The speed shaped more than just playback — it influenced composition. With only three to five minutes per side, musicians had to convey emotion, narrative, and musical complexity within tight temporal confines. Jazz improvisations were sharpened, blues storytelling distilled, and early pop songs meticulously structured. In a sense, the 78 RPM record didn’t merely capture music — it taught music how to exist.

Shellac, Sound, and the Magic of Imperfection

Vinyl enthusiasts often speak of warmth, but 78s possess a different kind of sonic magic. Shellac, the brittle resin used in these discs, produces a crisp, raw sound rich with harmonic textures and subtle distortions. Every pop, click, and crackle is more than noise — it is character, history, and memory embedded in grooves.

Under a microscope, a 78’s groove twists like a miniature landscape, encoding vibrations that a needle transforms into audible emotion. Unlike modern vinyl, which strives for uniformity, shellac records bear the fingerprint of the craftsman, the whims of the pressing plant, and even minor environmental changes like temperature and humidity. Playing a 78 is hearing music through the lens of its creation.

Digital reproductions often flatten this experience. Even high-quality vinyl reissues cannot replicate the unpredictable textures, the tiny inconsistencies, and the tactile intimacy of a shellac pressing. A 78 is more than a recording — it is a mechanical performance frozen in time, waiting for a needle to breathe it back to life.

Cultural Pulse: 78s Around the World

78 RPM records were not only technological achievements — they were vehicles of cultural exchange. Jazz leaped from New Orleans to Paris. Blues traveled from the Mississippi Delta to London parlors. Folk songs crossed oceans and continents.

The format’s limitations — brevity, fragility, and speed — shaped the music itself. Artists learned to tell stories quickly, to craft hooks that lingered after mere minutes. Many songs we consider timeless were written to fit the mechanical boundaries of a machine. Without 78s, the architecture of modern pop, jazz, and blues might be fundamentally different.

Collectors and DJs today prize these discs for rarity and texture. Test pressings and private editions, often never reissued, offer glimpses of performances long forgotten. Modern musicians and experimental sound artists sample 78s for loops, textures, and crackles that are impossible to generate digitally. In these grooves, the past meets the present in ways that are both sonically rich and culturally profound.

Revival and Preservation

Despite their decline after the mid-20th century, 78s have experienced a quiet renaissance. Archivists, collectors, and experimental musicians recognize them not as obsolete relics, but as living artifacts.

Audiophiles chase the shellac’s signature sound. DJs and sound designers exploit the harmonic richness and crackle for texture. Archivists study stylus sizes, playback speeds, and groove geometries to digitize recordings with scientific precision, preserving sonic history with astonishing accuracy.

Playing a 78 today is almost ritualistic. Each disc demands careful handling, meticulous cleaning, and precise playback speed. Minor deviations in pressure or RPM can alter pitch, tone, and timbre. In a digital age of effortless streaming, the 78 reminds us that presence, patience, and touch are part of the musical experience.

Hidden Stories in Dead Wax

Beyond the music, 78s carry secrets in the dead wax — the area near the label. Engineers and pressing plants etched matrix numbers, signatures, or cryptic messages, often unnoticed by casual listeners. These micro-details transform each disc into a narrative object, a conversation across decades.

Listening to a 78 becomes a multi-layered experience: the music itself, the physical artifact, the hidden inscriptions, and the echo of human hands that shaped it all. It is auditory archaeology, where every crackle and pop carries historical context.

Why 78s Still Matter

78 RPM records are more than nostalgia — they are lessons in creativity under constraint, artifacts of global culture, and experiments in the interplay of technology and artistry. They challenge modern musicians and listeners to remember that limitations can foster genius, that fragility can convey intimacy, and that the tactile, mechanical world still has a place in the age of digital perfection.

Holding a 78 is an encounter with history, science, and art all at once. The grooves spin stories of a world that is gone but echoes in every note. In that fragile, spinning disc, music is alive in a way that no stream, download, or even modern vinyl pressing can replicate.

Conclusion: Spinning Time

So, the next time you see a 78, slow down. Place the needle carefully. Listen not just to the notes, but to the echoes of time: the hum of early engineering, the resonance of human hands, the fleeting perfection of a performance captured in a fragile shellac disc. 78 RPM may have been replaced by more convenient formats, but its spirit endures — crackling, raw, and utterly alive.

To play a 78 is not just to hear music. It is to spin history, touch culture, and feel the heartbeat of an era that still pulses beneath the grooves.

Sources: This article was written based on the author’s personal knowledge and passion for vinyl records, drawing from years of independent learning and experience, rather than specific external sources.

Teresa Catita

Editor and Writer