So, what is a poverty trap? At first glance, we can perceive that it associates a notion of persistency or inevitability with poverty. Well, a trap is, in fact, a situation in which one gets into, and from which it is difficult or even impossible to escape. So, to put it in a simple manner, let us use the case of the “nutrition-based poverty trap,” originally portrayed in the Dasgupta and Ray paper.

The common person will need food to perform their daily tasks and earn money, which, in turn, allows them to sustain their own existence. Take the case of a person with no energy or nutrients left in their body; certainly, the first few calories they ingest are going to be consumed by their body just to survive: they will not make her strong! Once the person starts to eat enough to survive, the following calories ingested will give her strength and energy to perform other activities. Thus, someone in poverty may not have enough to eat to become very productive, but if she could eat more, she would.

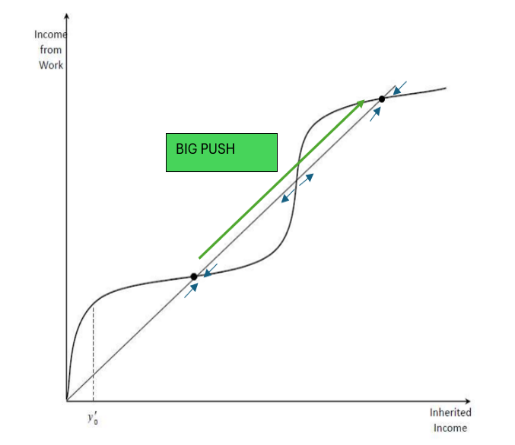

This portrays exactly the notion of the poverty trap, understood as self-reinforcing mechanisms whereby poor individuals or countries remain poor. Departing from the observation that poverty begets poverty, in such ways that current poverty can itself be a direct cause of poverty in the future.

But, why care about poverty traps? Because being in the presence of a poverty trap opens the possibility for a “Big Push”: a single push that could have disproportionately big benefits. Some examples, that have materialized, are the distribution of free bed nets, which carry massive health benefits regarding disease spread, namely malaria prevention; And the increased productivity gains for a community that a single season of free fertilization of fields can bring. However, it is necessary to understand that if we are not in the presence of a poverty trap, then providing help to those in poverty in this way will become a form of redistribution, but it won’t produce efficiency gains.

As bluntly put by Aart Kraay and David McKenzie, the idea of a poverty trap is very compelling in terms of motivating policy, because it suggests that people and countries may not only be unable to climb out of poverty on their own. But also, that much poverty is needless in the sense that a different equilibrium is possible at a much higher level of income and that one-time policy efforts may have lasting effects.

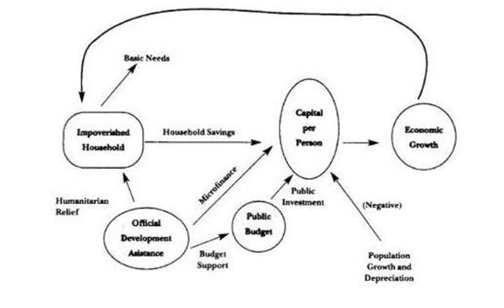

Let’s move now to the concept of Foreign Aid. The Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of OECD defines Official Development Assistance (ODA) as: “The flows provided by official agencies, including state and local governments, or by their executive agencies, to countries and multilateral institutions, that are administered with the objective of promoting economic development and welfare of developing countries.”

The aid debate: Context

To better understand the debate around Aid, one should first examine its origins, or better yet, the context in which it occurred.

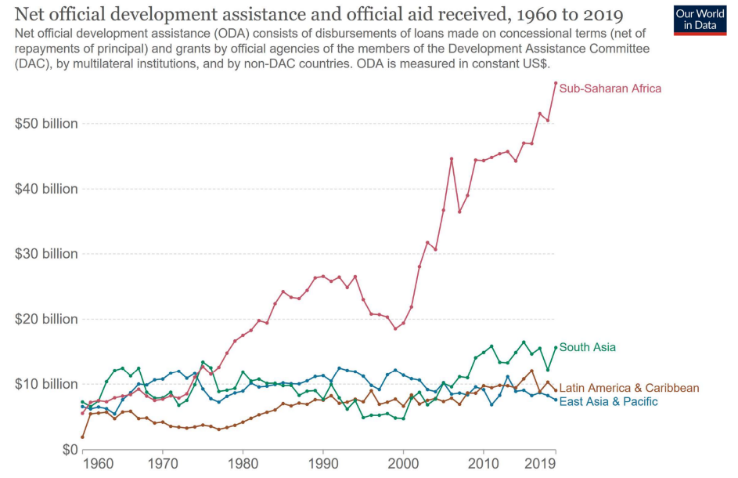

The Aid legitimacy crisis in the 90s emerged because of significant shifts in the international landscape. Following the end of the Cold War, the political foundation of bilateral aid underwent a profound transformation as the focus shifted towards aid’s economic effectiveness. Moreover, the 90s saw donor countries grappling with economic crises and strong budgetary constraints, particularly EU countries, which led to a sharp fall in aid flows. At the same time, recipient countries started to face increasing debt burdens and financial crises of their own. This sparked the broader debate over the need to reform the international aid architecture, particularly reshaping the role played by multilateral institutions in addressing the root causes of instability in recipient countries.

Positions: Is Aid Effective?

The 90s marked the beginning of a period where questions arose about the efficacy of the existing aid mechanisms and three main positions on the role of Aid emerged:

- AID ENTHUSIAST

The first position, by the American economist Jeffrey Sachs, emphasizes how poverty stems from a lack of six crucial types of capital: Natural, Human, Infrastructure, Public institutional, and Knowledge capital. Sachs argues that governments should offer extensive Aid to these areas because of the existence of natural monopolies in essential services, like power and transportation, public goods that benefit everyone without depleting resources, externalities, such as disease prevention and education, that have widespread benefits and that societies worldwide aspire to ensure universal access to critical goods and services as a fundamental right.

One example of a successful large-scale policy was “The Green Revolution”: when the Rockefeller Foundation promoted high-yield varieties, of staple crops, fearing a massive hunger in more rural populations. Mexico went from a large net importer of grain to a large net exporter in just 20 years and India followed in its footsteps, going from 11m tons of wheat production in 1960 to 55m tons in 1990.

Sachs proposes the Millenium Development Goals as the solution. The programme establishes that poor countries have no guaranteed right to receive assistance from rich countries to meet the MDGs, with this right conditional on countries’ commitment to good governance. However, the biggest problem today is not that poorly governed countries get too much help, but that the well-governed ones get far too little.

- THE DEATH OF AID

The second position, developed by the Zambian economist Dambisa Moyo, identifies aid dependency as the major obstacle to progress. She notes how, despite African countries having received over US$300 billion in development assistance since 1970, aid-dependent countries have experienced negative economic growth, and poverty rates have skyrocketed up to 60% in the same period, up until 1998. Moyo contends that aid inflows exacerbate problems in African nations by reducing government accountability to taxpayers, discouraging entrepreneurship and innovation, and fuelling corruption and conflict.

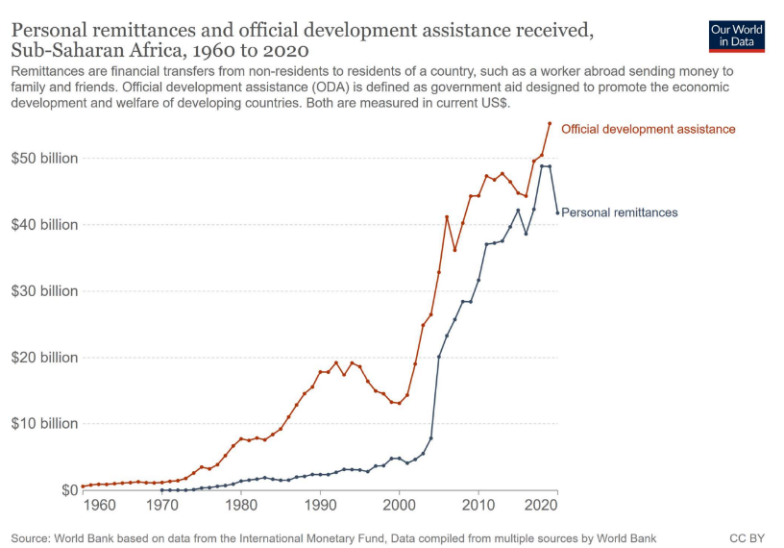

Figure 2- The impact of remittances.

Contrasting the African landscape with the success of Asian emerging markets, Moyo suggests as alternative strategies the access to international bond markets, and the attraction of large-scale direct investment in infrastructure, such as the Chinese investment policies. Moyo also advocates for genuine free trade in agricultural products, by ending farmer subsidies in major economies like the US, EU, and Japan and the promotion of financial intermediation, fostering the spread of microfinance institutions, granting legal titles to property for use as collateral, and facilitating remittances.

- AID BACK IN THE POLICY MENU

The third and final perspective is presented by the British economist Paul Collier, who views aid as a fundamental part of a broader strategy for addressing global challenges. Directly advising policymakers on the issues concerning the “Bottom Billion”, Collier identifies 4 Traps that hinder development:

1. “The conflict trap”: Many of the world’s poorest countries are trapped in cycles of violence and conflict, which disrupt economic development and perpetuate poverty. “73% of people in the societies of the bottom billion have recently been through a civil war or are still in one”. 2. “The natural resource trap”: Countries rich in natural resources often suffer from commodity price volatility, political checks, and deteriorated balances as accountability deteriorates. 3. “The Landlocked trap”: countries that are landlocked face significant challenges in accessing global markets, which hinders their ability to trade and grow economically. “While in the World as a whole only 1% live in landlocked resource-scarce areas, in Africa, that same percentage goes up to 30%”. 4. The trap of bad governance in small countries, as in small countries, the government necessarily plays a larger role in guiding economic development.

To address these same challenges, Collier suggests four main tools:

1. Targeted aid programmes to help alleviate poverty and address the root causes of underdevelopment. 2. Military intervention, is necessary for maintaining peace in post-conflict situations and preventing coups. 3. International agreements and legal frameworks that can help address issues such as corruption, resource management, and governance. Examples include the Kimberley Process for diamond certification, aimed at curbing the trade in conflict diamonds. 4. Reforming trade policies in the West (“Rich countries’ trade policies” include agricultural subsidies to their own sectors and higher tariffs for processed materials) and Improving access to global markets.

Is Aid effectiveness supported by the data?

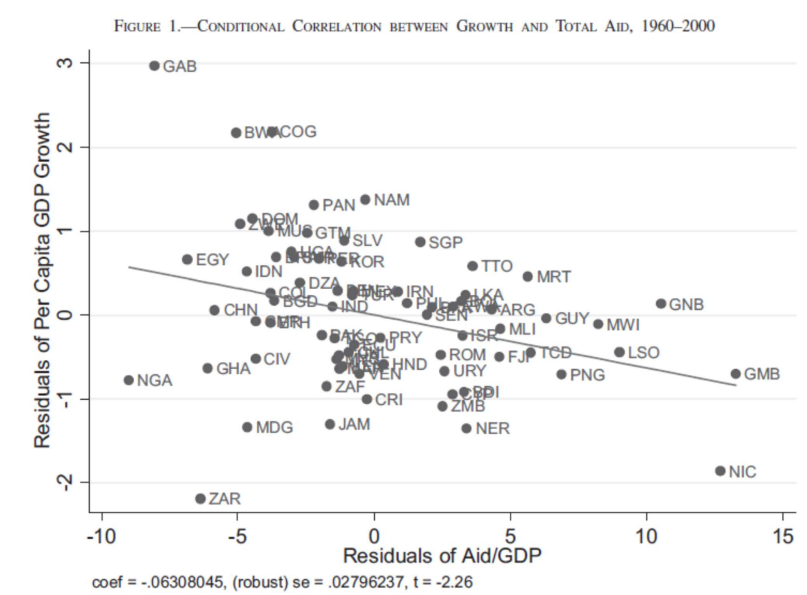

Although relevant, these three positions are simply the theories of their authors. Thus, to have a more comprehensive understanding of the issue around aid, one must observe what the real data reveals. Many studies have been developed regarding the effectiveness of Foreign Aid. In this article, only the Rajan and Subramanian paper on Aid and Growth will be referred to as its data gives comprehensive coverage of all variations of the aid-growth relationship.

One of the key findings of their analysis was that the relationship between aid and economic growth is complex and context-dependent: there is evidence that aid works better in better policy or geographical environments, and that certain forms of aid work better than others. This brings out the need to move away from one-size-fits-all approaches to foreign aid and instead tailor interventions to the specific context and needs of each country. Rajan and Subramanian also observe little robust evidence of a positive relationship between ODA inflows into a country and its economic growth. Thus, empirically, no conclusions can be made regarding the relationship between both variables.

Overall, diverging political views on the role of aid bring dynamism to the Foreign Aid debate. Although one position is yet to be selected as “the right one”, it is easy to see how they can be complementary to each other. They have inclusively been the root of many projects that have already improved people’s lives, with Sachs’s preferred example remaining “The Green Revolution”. So, before deciding whether Aid carries efficiency gains and other benefits for developing economies, keep in mind, as prize winner Esther Duflo once said: “Innovation often comes from unexpected sources; we should be open to diverse perspectives and ideas.”

Sources: Duflo, Esther, and Abhijit Banerjee. Poor economics. Vol. 619. New York: Public Affairs, 2011. Kraay, Aart, and David McKenzie. “Policy Research Working Paper 6835.” Policy (2014). Dasgupta, Partha, and Debraj Ray. “Inequality as a determinant of malnutrition and unemployment: Theory.” The Economic Journal 96, no. 384 (1986): 1011-1034. Collier, Paul. The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it. Oxford University Press, USA, 2008. Rajan, Raghuram G., and Arvind Subramanian. “Aid and growth: What does the cross-country evidence really show?” The Review of economics and Statistics 90, no. 4 (2008): 643-665. This article was built on slides by Victoire Girard.

Catarina Ribeiro