It would be possible to end poverty in the United States, at least in theory. Using a pure means-tested transfer system, the authorities could compensate each individual in the amount remounting the difference between the poverty line value and their income. This would cost only 131 billion dollars, about one-sixth of the value cost of the Social Security program (Using the U.S. Bureau of the Census 2019). The problem is that such computation doesn’t account for the Moral Hazard implications that come with benefit guarantees, as Jonathan Gruber points out in his book Public Finance and Public Policy (2019, Chapter 17).

What happens is that this program may have a way of disincentivizing work to some extent, as it can motivate people slightly above the poverty line to stop working to receive the full benefit without substantially having to lower their consumption. Thus, increasing the number of people receiving the benefits, along with the policy’s costs.

This phenomenon, named Moral Hazard, largely studied by economists, constitutes a change in people’s behavior provoked by the acquisition of insurance, either literally or figuratively speaking. In economics, this event usually leads to inefficient allocations of resources since it induces individuals to have a consumption different from the optimal level. The most common examples of Moral Hazard situations are observed in public policy, such as in the scenario described above, with insurance-related issues, such as health insurance or car insurance, and even during the Great Recession, the topics for the discussion in this article.

Illustration by Christoph Niemann, The New Yorker

Moral Hazard in Public Policy

There are multiple applications of this concept within the realm of insurance in public policy. Unemployment, disability, injury, retirement, and poverty, appear as somewhat unpredictable situations against which agents want to be insured. If one is to think about it, much of the population seeks to smoothen their consumption throughout life. This can be translated into preferring to pay a fixed amount in insurance premiums so as to benefit from compensation in the face of an adverse event, like job loss, in such a way that consumption does not brutally fall.

Here, Moral Hazard usually conveys disincentives to work: Take the example of Unemployment Insurance (UI), that functions as a means of compensating individuals if they lose their jobs. If the payment amounted to 100% of workers’ salaries, people would not have the incentive to seek employment throughout the duration of the benefit, which would ultimately lead to a lower-than-optimal provision of labor in the economy. Additionally, much of the workforce would have an incentive to stop working, adding up to the costs of the program. This is why not only UI but also schemes that cover these and other types of adverse events often do not contemplate full insurance. Instead, they try to weigh out the consumption smoothing ability that the program carries with its Moral Hazard costs.

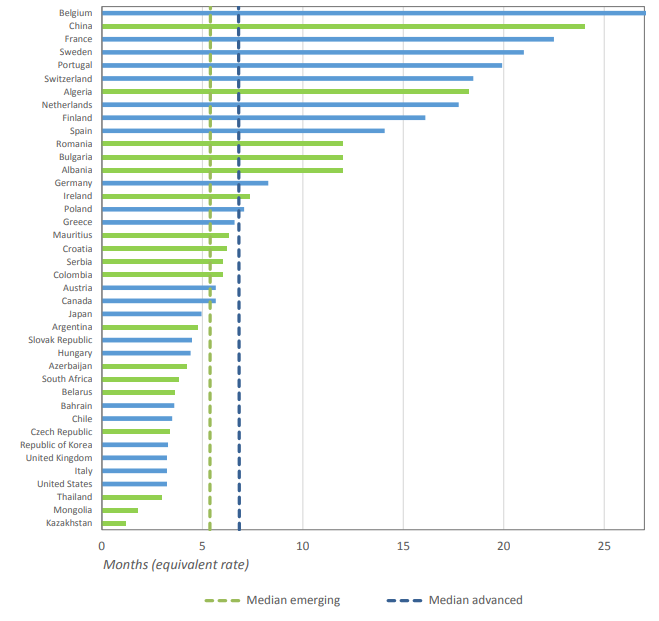

Countries may choose different schemes of Unemployment Benefits, depending on their internal policies. According to the Figure, it can be pointed out that the United States provides one of the lowest financial disincentives to return to work and constitutes one of the countries with a lower maximum amount for the duration of the benefits program (Figure 2). On the other hand, in most European countries the disincentive is more substantial and the threshold for the benefits is higher.

Fig.1 – Financial disincentive to return to work (2023, OECD Data)

Fig. 2 – Maximum duration of unemployment benefits at an equivalent rate (2019, ILO)

Moral Hazard in Health Insurance

Once again, insurance (in the health case) promotes consumption smoothing when faced with an adverse event (sickness). Its importance relates to the fact that it facilitates necessary treatments without the injured having to carry out major payments.

Yet, another common means for Moral Hazard to manifest itself is through health insurance, which can comprise two types: Ex ante and ex post Moral Hazard. The first one illustrates cases where individuals have less incentive to indulge in activities that reduce the risk of sickness or illness (e.g. smoking), when insured, whereas the last comprises a circumstance in which insurance beneficiaries are less likely to limit the use of healthcare when sick (e.g. going to consultation because of a cold).

When provided with health coverage, individuals may be more prone to seek medical care for minor conditions or undergo unnecessary procedures. This overutilization can strain healthcare resources, and lead to inefficiencies in the delivery of care. Additionally, it can drive up costs for insurers, leading to greater insurance premiums.

However, would it be unreasonable to assume this increase in healthcare utilization can come from the actual need for medical care?

“Too Big to Fail”: Moral Hazard in the Great Recession

Moral Hazard is not only present in the daily life of the average person but also in the most pressing global financial crises. The most prominent example being the 2008 Financial Crisis. In the years leading up to this crisis, the United States had evidenced an exponential increase in housing prices, stemming from factors such as the accessibility of credit, lower interest rates, and permissive lending standards. This allowed a significant number of subprime borrowers to obtain mortgages, bundled by Financial Institutions to form Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) and Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO) which were posteriorly sold to international investors with higher credit ratings.

Why did Financial Institutions engage in such risky lending practices?

Credit rating agencies played an instrumental role in the crisis by assigning high ratings to MBS and CDO, prompting a false sense of security about the degree of risk of these securities. This is where Moral Hazard comes in, as the financial institutions involved operated in accordance with the misbelief that they were “too big to fail” (Stewart McKinney, 1984). This entailed the expectation that, because of financial institutions’ vitality to the economy, regulating authorities would not allow them to fail due to the systemic risk that could influence the course of the global environment. Thus, these continued to operate with disregard for possible unfavorable outcomes so, when housing prices peaked and proceeded to decline in 2006, borrowers defaulted on their mortgages, leading to a collapse in the value of MBS.

The losses caused a domino effect in the financial sector and major financial institutions faced bankruptcy, with long-lasting effects on the global economy prompting a significant need for regulatory reforms. One measure was the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform which implicates more strenuous capital and liquidity requirements for banks with at least $50 billion in assets, and the Consumer Protection Act in the US to further protect financial activity in the country. Its provisions included the Volcker Rule, which argues that banks that take on hazardous risks should not be government-subsidized and aims at constraining banks from using their own money to trade securities, rather than depositor money. The latter faced opposition as many of the institutions that integrated this failure did not take on deposits and would not have been subject to such rules.

So, are authorities able to contain Moral Hazards?

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), a bank with assets totaling $209 billion in late 2022, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, collapsed one week after being listed on Forbes’ America’s Best Banks List, making the sour transition from one of the best American banks, into the second-largest bank failure in US history.

This unfortunate occurrence sprang from the large amount of deposits with scarce cash held by the bank, with which SVB would buy treasury bonds and other long-term debts that have low returns and risk. However, as the Federal Reserve increased interest rates to combat inflation, SVB’s bonds became riskier and, thus, saw a stark decline in value which prompted mass customers to withdraw funds, leading to its collapse.

It is also argued that this failure started before the Federal Reserve’s regulations, with the overturn of the Dodd-Frank Act whose requirements were relived in 2018 by former President Donald Trump. This was done through the Economic Growth Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act, according to which the law increased the threshold to $250 billion. Thus, another instance of moral hazard lies with the bailout provided to SVB, raising concerns regarding other banks’ propensity to take risks. It is, therefore, of great importance to acknowledge the dichotomy faced by the Federal Reserve when weighing price stability and financial stability, since interest rates, despite being conventionally perceived as a powerful strategy to stabilize inflation, can rapidly escalate to become a trigger for Moral Hazards within the financial sector, rooting global financial instability.

Policy implications

Evidently, public policy applications of Moral Hazard come with implications. Many economists focus their work on the design of these. With the UI, policymakers try to balance the consumption smoothing benefits of the insurance with its Moral Hazard costs, which depend on the magnitude and predictability of adverse events. For example, retirement is a rather predictable event, so people may prepare in advance. On the other hand, unemployment is considered of low magnitude, meaning that some may be able to self-insure. The functioning of both Disability Insurance (DI) and Workers’ Compensation (WC) goes along those lines, which ultimately impedes these programs from offering full coverage.

Poverty alleviation programs, as mentioned in the introduction, also carry Moral Hazard concerns. In such a case, there are policies designed to try to make sure that everyone who needs the benefit gets it and those who do not don’t, although this might be difficult. There are some instruments impregnated in society to try to regulate this, such as ordeal mechanisms, that make welfare programs somewhat unattractive to guarantee that only the population that necessitates benefits from them. For example, the long lines in soup kitchens.

In 2010, President Barack Obama signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, often referred to as the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or Obamacare. This legislation aimed to extend health coverage to millions of uninsured Americans by expanding Medicaid, establishing health insurance exchanges, and introducing various health-related provisions. The ACA sought to make health insurance more accessible and affordable. It offered premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions to individuals with lower incomes. However, the Act may also have exacerbated existing moral hazards within the health insurance industry, as Sean Ross discusses in his article (2023). Some of the provisions included the mandatory coverage of some essential benefits, the obligation to buy insurance, provided with an exemption for low-income citizens, and restricting prices. However, in such a scenario, one should also consider the fairness argument for the existence of programs that lower the efficiency of an economy. At the end of the day, it is a trade-off.

Illustration by Andrew Grossman, IAS

Conclusion

From work disincentives to devastating financial crises, moral hazards’ ever presence within a country’s economy underscores the intricacy in policy making towards a balance between social welfare and economic efficiency. While initiatives such as healthcare or social benefits aim to mitigate disparities, moral hazard reminds governments of the complexity implicit in policymaking and surfaces the question introduced in this article: To moral hazard or not to moral hazard?

References

Aklin, Michaël, and Andreas Kern. 2019. “Moral Hazard and Financial Crises: Evidence From American Troop Deployments.” International Studies Quarterly (Print) 63 (1): 15-29. https://academic.oup.com/isq/article/63/1/15/5290056

Asenjo, Antonia, and Clemente Pignatti. 2019. Unemployment insurance schemes around the world: Evidence and policy options. ILO Working Paper no 49 (October): 20-24 https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—inst/documents/publication/wcms_723778.pdf

Dewan, Shaila. 2012. “Moral Hazard: A Tempest-Tossed Idea” The New York Times. February 25, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/26/business/moral-hazard-as-the-flip-side-of-self-reliance.html

Duggan, Wayne. 2023. “A Short History of the Great Recession.” Forbes Advisor, June 21, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/great-recession/

“Financial Crisis and the Ethics of Moral Hazard on JSTOR.” n.d. Www.Jstor.Org. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24575743

Gruber, Jonathan. 2019. Public Finance and Public Policy, 6th Edition, Chapters 14, 15, 17. New York: Worth Publishers

OECD (2024). Financial disincentive to return to work (indicator). https://data.oecd.org/benwage/financial-disincentive-to-return-to-work.htm#indicator-chart

Ross, Sean. 2023. The Affordable Care Act Affects Moral Hazard in the Health Insurance Industry. Investopedia. 2023. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/043015/how-does-affordable-care-act-affect-moral-hazard-health-insurance-industry.asp

Stiglitz, Joseph. 2023. “Silicon Valley Bank’s Failure Is Predictable – What Can It Teach Us?” The Guardian, March 13, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/mar/13/silicon-valley-bank-failure-svb-collapse

SVB: US Regulators Have Generated a ‘Moral Hazard.’” n.d. The Banker. https://www.thebanker.com/SVB-US-regulators-have-generated-a-moral-hazard-1679645486

Team, Investopedia. 2023. “How Did Moral Hazard Contribute to the 2008 Financial Crisis?” Investopedia. October 26, 2023. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/050515/how-did-moral-hazard-contribute-financial-crisis-2008.asp

The Economist. 2017. “How The 2007-08 Crisis Unfolded.” The Economist, June 8, 2017. https://www.economist.com/special-report/2017/05/04/how-the-2007-08-crisis-unfolded

Madalena Martinho do Rosário

Maria Francisca Pereira