We live in an era of extraordinary abundance. At any moment, people are exposed to far more alternatives than previous generations did, across nearly every domain in life. The world has never offered so much choice, yet many individuals feel increasingly overwhelmed by it.

Psychological research suggests that, while choice is essential for autonomy and well-being, too many options can have the opposite effect on decision-making quality and satisfaction. This phenomenon challenges the assumption of classical economics that more alternatives lead to better outcomes.

The psychology of choice overload

When confronted with a large number of alternatives, individuals often experience difficulty in making decisions, a tendency known in literature as choice overload or overchoice.

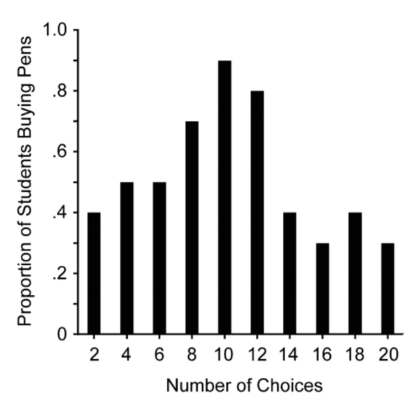

One of the earliest and most cited demonstrations of this effect was the so-called “jam experiment” conducted by psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper. In their study, shoppers at a local market were presented with either 24 varieties of jam or just 6, and while more customers stopped at the larger display, far fewer made a purchase compared to those who saw fewer options.

This counterintuitive result highlights a central paradox: abundance of choice can reduce the likelihood of a decision being made at all. The cognitive load associated with evaluating too many alternatives can lead to what psychologists identifiy as decision paralysis, where individuals delay or avoid making any choice due to overwhelming complexity.

In this context, research points to additional consequences of choice overload, including increased stress, regret for forgone options, and lower confidence in the choices that are made.

The cognitive cost of choice overload

From a neuroscientific perspective, decision-making consumes cognitive resources. In particular, the prefrontal cortex, often described as the brain’s executive center for planning and evaluation, plays a significant role in choosing among alternatives. As the complexity of options increases, so does the mental effort required to process information and make judgments, defined as cognitive load. When faced with an excessive number of alternatives, this increased load can exceed working memory capacity, leading to mental fatigue and suboptimal choices.

In extreme cases, prolonged decision-making under such conditions can trigger what psychologists term decision fatigue, a decline in decision quality that arises after repeated cognitive exertion during choice tasks. Importantly, decision fatigue often results in a shift toward simpler heuristics or impulsive reactions based on biases, rather than thoughtful deliberation.

How the digital era multiplies our choices

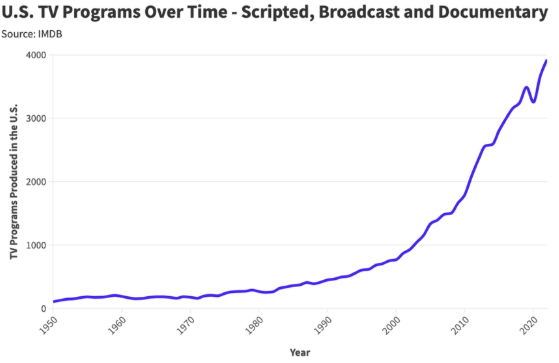

In the digital era, choice overload permeates everyday life: a typical online marketplace now offers thousands of products, each often presenting mulitple ratings, features, and reviews. Streaming services aggregate tens of thousands of titles, and users often report spending more time choosing what to watch than actually watching.

Even outside market-based decision environments, people face an ever-expanding range of alternatives in careers, travel destinations, social interactions, and financial decisions. Behavioral economists and psychologists note that this proliferation of options can paradoxically diminish overall satisfaction and confidence in one’s choices. This trend also shapes broader macroeconomic dynamics. When choices become overwhelming, people participate less actively in markets, often stepping back from decisions altogether. Evidence from e-commerce illustrates that when faced with an excess of product options, many consumers simply postpone or abandon their purchases.

The human cost of abundance

Although choice is often associated with autonomy and freedom, an excess of options may lead to psychological downsides. One well-studied distinction in literature differentiates between “maximizers”, individuals who seek the best possible option, and “satisficers”, those who settle for good enough. When faced with abundant choices, maximizers tend to experience higher levels of regret, lower satisfaction, and greater decision anxiety than satisficers.

Further research suggests that an abundance of choice can even undermine self-control and promote impulsive behavior, particularly after making repeated decisions. This effect has been documented in studies showing that frequent decision-making can deplete mental resources, leading to cognitive and emotional fatigue.

Beyond individual psychology, widespread choice overload may contribute to broader societal patterns of stress and dissatisfaction. Rather than eliciting joy, the freedom to choose can inflate expectations and intensify regret, particularly when people believe a better choice was possible.

Toward smarter choices

Despite its potential drawbacks, choice is still a fundamental part of our lives and need not be feared. A growing body of research indicates that individuals can navigate abundant options more effectively through strategic decision frameworks and environmental design. For example, consciously limiting the number of alternatives under consideration, a practice known as pre-filtering, has been shown to streamline decision-making and reduce cognitive strain. Other helpful approaches include setting clear criteria before engaging in selection, focusing on satisficing rather than maximizing when faced with many options, and using structured heuristics that prioritize key attributes over exhaustive comparison.

Behavioral economists refer to these techniques collectively as part of choice architecture, which aims to structure decision environments in ways that support better outcomes without eliminating freedom of choice.

Conclusion

The paradox of choice illustrates a key tension in modern life: while freedom and autonomy are deeply valued, an excess of options can undermine the satisfaction and confidence individuals seek. Across consumer behavior, digital decisions, and everyday life, too many alternatives can lead to fatigue, regret, and disengagement.

Understanding the psychological and neural mechanisms behind choice overload does not require rejecting freedom, but rather it leads to a more intentional relationship with our decisions.

Sources: When Choice is Demotivating: Can One Desire Too Much of a Good Thing? by Iyengar & Lepper (Journal of Personality and Social Psychology); The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less by Schwartz; Why Do We Have a Harder Time Choosing When We Have More Options? by The Decision Lab; On the Advantages and Disadvantages of Choice: Future Research Directions in Choice Overload and Its Moderators by Misuraca, Nixon, Miceli, Di Stefano, Scaffidi, Abbate (Frontiers in Psychology); Choice Overload: A Conceptual Review and Meta-Analysis by Chernev, Böckenholt, Goodman (Journal of Consumer Psychology); Decision Fatigue in E-Commerce: How Many Product Options Are Too Many? by Winsome Writing Team (Winsome); The Paradox of Choice: How Too Many Options Affect Consumer Decision-Making by Winsome Writing Team (Winsome).

Margherita Ottavia Serafini

Writer