The gender pay gap index is often perceived as a clear and straightforward indicator of inequality: the lower the gap, the more equal a society must be. Yet, when looking at European data, this assumption immediately breaks down. Countries widely recognized for their strong gender equality, such as Finland and Denmark, show some of the highest gender pay gaps in Europe, respectively of 16.8% and 14.0% in 2023. Conversely, Southern European countries, typically portrayed as less advanced in terms of labor equality, often show lower gaps, such as 2.2% in Italy, 5.1% in Malta and 8.6% in Portugal.

This counterintuitive pattern raises a key question: why do some of the most gender-progressive countries display such large pay gaps?

Understanding the answer requires unpacking what the gender pay gap actually measures and how structural factors shape the interpretation of the data.

A counterintuitive European puzzle: how labor participation affects the gender pay gap

According to Eurostat, the gender pay gap represents the average difference between male and female hourly earnings across an entire economy. However, this “raw” indicator does not adjust for variables such as employment rate, seniority, working hours, occupation, or industry composition. As a result, countries with very different labor market structures can produce misleading pay gap figures.

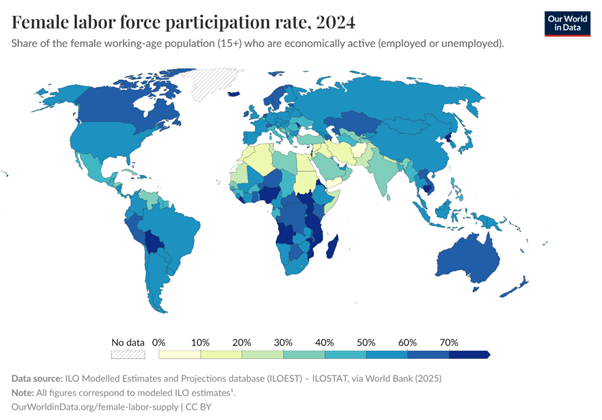

In the European context, Nordic countries display among the highest female labor participation rates in Europe. In Sweden and Finland, around 75-77% of working-age women are employed, compared to roughly 52% in Italy, according to the Eurostat data for 2021. This fundamental difference has two statistical consequences:

(1) More women participate across many sectors, including high-paying but male-dominated private industries, where pay disparities are more apparent.

(2) In low-participation countries, many women who would earn less or face structural disadvantages simply do not appear in the labor market statistics.

This means that a “low pay gap” can reflect fewer women working, not more equal pay.

Structural factors shaping the gender pay gap

A low pay gap may also reflect structural constraints, cultural norms, or barriers that discourage women from entering specific sectors, or even from participating in the workforce altogether. In Italy, for instance, women are underrepresented in high-earning private-sector roles but are comparatively overrepresented in stable public-sector professions, where pay scales are more regulated. This combination tends to compress wage differentials and therefore “artificially” decrease the gender pay gap.

By contrast, in Nordic countries women participate across a wide range of sectors, including those with substantial wage dispersion. This results in a broader and more accurate representation of gender differences in earnings.

In this sense as well, a low pay gap is not inherently a sign of gender parity.

The role of part-time work and occupational segregation

A third major factor explaining the higher gender pay gaps in Northern Europe is the prevalence of part-time employment among women. According to Eurostat, countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark have some of the highest female part-time rates in Europe, compared to Southern European countries like Portugal, Greece, or Spain. Part-time jobs tend to be paid less per hour, offer fewer opportunities for career progression, and limit access to high-responsibility roles. Although part-time work in these countries is often facilitated by supportive family policies and may be a voluntary choice, it nevertheless contributes significantly to the gender pay gap.

This pattern results in greater salary divergence between genders, even in settings where equality norms are strong.

The Nordic Gender Equality Paradox: when generous policies widen the gap

One of the most discussed phenomena in economic literature is the Nordic Gender Equality Paradox. Although, as previously mentioned, Nordic countries consistently lead global rankings on gender equality, research by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) has shown that highly generous parental leave policies can unintentionally amplify long-term differences in earnings.

In countries such as Sweden, Denmark, and Finland, parental leave systems are among the most comprehensive in the world. While these policies ensure high levels of family wellbeing, they often result in women taking longer leave periods than men, leading to a slower re-entry into the labor market. This does not suggest that generous welfare policies are harmful; rather, it highlights how well-intentioned reforms can produce unintended labor-market outcomes when uptake remains uneven across genders.

In Nordic countries, despite continued efforts to encourage paternity leave, women still take the vast majority of parental-care responsibilities. This persistent imbalance shapes career progression and contributes to long-term differences in lifetime earnings trajectories.

Why public perception gets it wrong

Public understanding of the gender pay gap is often shaped by simplified narratives, headlines, or assumptions based on cultural stereotypes about specific regions. Surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center show that people tend to overestimate gender differences in some contexts and underestimate them in others.

Many assume that Nordic countries must have both high labor equality and low pay gaps. While this is true in some dimensions, such as political representation, education, and labor participation, pay gaps capture a more complex picture involving sectoral structures, parental leave, part-time work, and long-term career dynamics.

Similarly, countries with low pay gaps are often assumed to be more gender equal, even though low participation rates, lack of childcare infrastructure, or rigid labor markets may paint a very different picture.

This disconnection between perception and reality underscores the importance of interpreting gender statistics with nuance and understanding what each indicator actually measures.

Conclusion

The gender pay gap is a useful measure, but understanding what underlies it is essential. As European data shows, a low gap does not automatically signal high equality, nor does a high gap inherently indicate poor conditions for women. Instead, the gender pay gap must be interpreted within the broader context of labor participation, occupational patterns, welfare policies, and family dynamics.

Nordic countries exhibit higher raw pay gaps because their labor markets include almost all women, across all sectors, roles, and wage bands, and because generous parental leave policies influence long-term earnings. Southern European countries show lower raw gaps largely because fewer women work and those who do tend to be concentrated in more regulated sectors.

A nuanced interpretation is therefore essential. Understanding the mechanisms behind the numbers allows policymakers, students, and future professionals to build a clearer picture of labor market inequalities. Only by looking beyond surface-level statistics can societies meaningfully address the structural causes of wage disparities and design interventions that move beyond appearances toward real equality.

Sources: Eurostat; OECD; The World Bank; CEPR – VoxEU: The Nordic Model and Income Equality: Myths, Facts and Policy Lessons by Mogstad M., Salvanes K. G., & Torsvik G.; World Bank Group, Gender Data Portal; European Commission; The World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report; The Economist: A Nordic Mystery; National Bureau Of Economic Research: The Child Penalty Atlas by Kleven H., Landais C., & Leite-Mariante G.; Pew Research Center, Global Attitudes on Gender Equality.

Margherita Ottavia Serafini

Writer