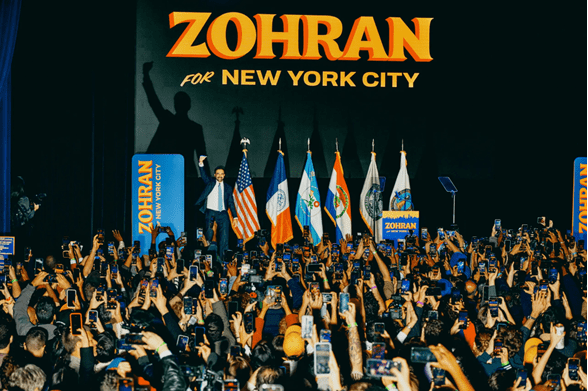

Zohran Mamdani was recently elected as the first socialist mayor of New York City last month. The city of Wall Street, billionaires and neoliberal globalization has just chosen a man who ran on a platform of housing justice, public transit, and redistributing wealth. “This isn’t just about New York,” Mamdani said during his victory speech in Queens. “It’s about imagining a different kind of future” (The New York Times, 2025).

NYC’s position as the United States’ largest city, and one of the world’s financial centers, is a strange bedfellow for an openly socialist politician. Some claim Mamdani’s victory represents the end of the neoliberal order within its home, yet others see it as a temporary response to exhaustion and inequality. However, it has opened a cultural conversation that stretches across the nation.

A Socialist in Finance’s Capital

New York has always been a paradox: the home of billionaires and of the homeless, of high art and unpaid internships. Its contradictions are almost part of its brand. Yet it has recently gone through rapid change. The global financial center of the 1990s, of hopeful entrepreneurs and mid-western dreamers who wanted to make it big, has been lost. In its place is an almost dystopian reality: crime, economic hardship for most, abusive rents with frozen salaries, and an air of tension and distrust of institutional change. Yet here was Mamdani.

Mamdani, born outside the US to an immigrant family, has spent years advocating for tenants’ rights and public housing (Burgis, 2025). His campaign focused on simple and popular ideas like rent freeze, free public transport, and reorienting city budgets towards public welfare (Reuters, 2025). In many ways, his election is the culmination of a cultural shift rather than a sudden revolution. Young voters, especially those under 35, have grown tired of capitalism’s unfulfilled promises. Rising costs of living, precarious work, and the digital age have made “socialism” no longer sound like a dirty word for American citizens (Pew Research Center, 2022). But was this truly a vote for socialism? Or simply a rejection of what came before?

Exhaustion and its Opportunity

Political scientist Michael Sandel once wrote that “populism arises when people feel humiliated by meritocracy” (Sandel, 2020). In New York, that humiliation took the form of unaffordable rent, crumbling infrastructure, and the sense that “success” was something reserved for the already successful. Analysts at The Atlantic argued that Mamdani’s victory was not a pure ideological triumph, but a reaction to systemic fatigue (The Atlantic, 2025). After decades of centrist mayors managing the city like a corporation, voters simply wanted something different.

Even Mamdani’s critics concede that his authenticity played a role. He biked to campaign events, and refused large corporate donations (The Guardian, 2025). Instead, he built a strong grassroots support, being present in communities, engaging with his support base directly, and being present. For many disillusioned citizens, he felt real. This presence helped bridge the gap between the voters’ perception of socialism. Mamdani’s win reflects that broader transformation. He talks less about class war and more about “belonging”. An emotional register that resonates in a fragmented digital age, especially with younger voters.

According to The New Yorker, his speeches mix activist language with pop-cultural references, a blend that feels “as Brooklyn as it is Marxist” (The New Yorker, 2025). This approach has helped him reach not only traditional leftists but also creative professionals and students who see themselves as progressive but not radical.

A Collapse or a Shift?

Is this the collapse of neoliberalism? Probably not. Neoliberal logic of competition, privatization, individualism still runs deep in American institutions. But culturally, the conversation has shifted, at least in urban areas. Mamdani’s rise suggests that alternative narratives are gaining legitimacy, especially among younger generations who grew up during crises rather than booms.

When news of Mamdani’s election started appearing, some warned of market instability. Yet the stock market barely moved (Bloomberg, 2025). Finance is apparently extremely pragmatic: as long as Mamdani doesn’t impose sudden regulation, Wall Street stays stable. So far, his administration has taken a targeted approach by ending some luxury tax breaks, introducing rent caps, and expanding public transport funding (City Journal, 2025). These policies are ambitious but far from revolutionary.

The US is still the economic powerhouse of the West, yet it is more apparently buckling under its own weight. Political tension is the highest it has been in the last 50 years, and it seems like something is brewing. Yet at the same time, its liberal institutions function in a similar way to capitalism: they allow voters to set the stage. The liberal order is strong in that way, it allows slightly different political ideas to test themselves in localised regions, before reabsorbing them into the fold. Mamdani’s politics are more democratic than socialist, and will not break with the Democratic’s party line of liberal democracy. Instead, he will serve as a political counterpart to conservatives in Washington DC: the new wunderkind, the shining light for democrats to follow.

Zohran Mamdani’s victory might not herald a new economic order, but it undeniably represents a new cultural mood: one where ideals of solidarity, justice, and public life are being reimagined. Can capitalism be “reformed” from within? Or must it be replaced by something else? Mamdani ‘s New York will prove a natural experiment for both questions.

Sources:

- ABC News. (2025, October 26). Mamdani rallies voters with support from Bernie Sanders and AOC [Photograph]. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/wireStory/new-york-mayoral-candidate-zohran-mamdani-rallies-voters-126888201 ABC News

- BBC Travel. (2025, November 3). What Mamdani’s win means for New York City’s food scene [Photograph]. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20251103-what-mamdanis-win-means-for-new-york-citys-food-scene

- Bloomberg. (2025, October 10). Markets steady after Zohran Mamdani’s surprise New York mayoral win. Bloomberg News. https://www.bloomberg.com

- City Journal. (2025, October 15). Mamdani’s Experiments Won’t Faze the Rich. Manhattan Institute. https://www.city-journal.org/article/zohran-mamdani-new-york-city-rich-business-wealthy-residents

- Burgis, B. (2025, November 5). Zohran is taking Bernie’s movement into the future. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2025/11/mamdani-sanders-economic-justice-socialism?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Lach, E. (2025, November 4). The Mamdani era begins [Photographs by Victor Llorente for The New Yorker]. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-local-correspondents/the-mamdani-era-begins The New Yorker

- Pew Research Center. (2022, September 19). Modest declines in positive views of ‘socialism’ and ‘capitalism’ in U.S. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/09/19/modest-declines-in-positive-views-of-socialism-and-capitalism-in-u-s/

- Reuters. (2025, October 5). DSA’s Mamdani wins NYC mayor race on progressive wave. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com

- Sandel, M. (2020). The tyranny of merit: What’s become of the common good? Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- The Atlantic. (2025, October 8). Why New York voted socialist: Fatigue, frustration, and hope. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com

- The New York Times. (2025, October 7). Zohran Mamdani elected first socialist mayor of New York City. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com

Lucas Bernal

Writer