Nearly ten years have passed since the eurozone was on the brink of collapse. In a moment where enthusiasm for the euro and the European project has climbed, as Europeans find a strange form of solidarity in the face of Brexit, it is easy to forget that for a few months in 2011 and 2012, the eurozone seemed to be about to fall apart.

Although the onset was sudden, the fragilities that were exposed on the eurozone crisis went far from unnoticed until then. In fact, in the lead-up to the introduction of the euro, in 1999, many prominent economists, among them Milton Friedman, judged the move towards the single currency as a mistake. Friedman wrote that it would “exacerbate political tensions” as divergent economic shocks would lead to difficulties in setting a eurozone-wide monetary policy stance. History would only prove him right.

Arguably, the eurozone’s troubles started even before its conception, as credit conditions between its members converged in antecipation of the euro’s introduction. As can be seen in the graph below, this was reflected in the government bond yields: by 2001, Greece paid out the same interest as Germany on its newly-emitted debt. The implied probability of default for the two countries was the same.

Although this may seem preposterous with the benefit of hindsight, at the time this was not seen as such a concerning development. There was a belief that in general, governance across the eurozone was becoming more similar, with countries being subject to the same incentives.

A development that could be in particular singled out was the elimination of currency risk. As countries like Greece no longer had control over the currency their debt is denominated on, and the “No Bailout” clause of the Maastricht treaty prevented the ECB from financing any particular country’s debt, eurozone members could no longer pay off their debt resorting to the printing press. This somewhat reassured investors, as they assumed this would force governments in the single currency area to adopt responsible fiscal policies.

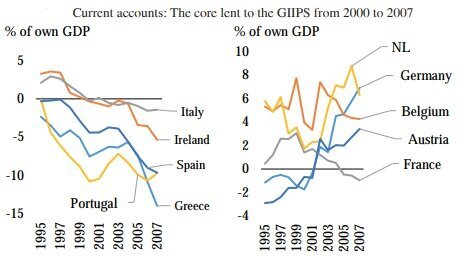

As credit conditions converged in the early years of the monetary union, there began an outflow of capital from the core of the euro area to the periphery. This can be seen from the graph below, which shows the current account balances of select eurozone countries in the period in question.

Source: WEO

Although it may seem surprising today, these flows of credit were contemporarily seen as success, as they were in accord with what economic theory predicted for convergence: the richer nations, where the returns on capital were lower, would lend to the poorer nations, which would catch up in terms of productivity as a result.

But any apparent real convergence was merely illusory, and these imbalances had perverse consequences.

Much of the investment in peripheral economies was squandered on non-traded sectors, such as construction, fueling housing booms, and government consumption. Since there was little build-up of export capacity, there was little hope of ever repaying external debt.

There was also a resulting widening of the competitiveness gap. As the credit boom in the peripheral countries of the eurozone resulted in an expansion of the construction industry, among others, excess demand for labour fueled above average wage inflation. Ironically, instead of promoting convergence among economies, the supposedly healthy imbalances were actually accentuating existing differences.

At this point, it might be important to note that unlike what is commonly believed, the core root of the crisis was not necessarily public debt. In fact, if we look at the figure above, we can see that in 2007 Ireland and Spain’s public debt-to-GDP ratios were actually far below Germany’s, which stood at 63.7%.

These two countries, however, saw instead excessive accumulation of private debt. This materialized in the form of excessive bank lending: for example, Irish banks had assets worth seven times the GDP of Ireland in 2007. This private debt also fueled housing bubbles, which made public debt ratios look better than the underlying conditions were, as significant chunks of GDP were based on highly speculative construction. These liabilities later overflowed into the governments’ balance sheets, as banks went bankrupt and had to be propped up by sovereigns.

In light of these excesses, it was a matter of time until all this leverage unraveled. In October 2009, the new Greek government revealed that the government deficit was much higher than previously thought. While the draft target set by the European Commission in 2008 for 2009 was a deficit of 1.8% of GDP, the final figure ended up being 15.6% of GDP. At this point, financial markets understandably started to panic about Greece’s ability to pay off its debt. The Greek spread over the German Bund started to climb.

Greece, in a last ditch attempt to save itself from ruin, agressively engaged in austerity measures, cutting spending and raising taxes, but this worked against its purpose. As the fiscal stance became more contractionary, economic growth, already feeble, slowed, and creditors started losing faith in Greece’s ability to repay. The spread kept getting higher, and the first bailout became inevitable.

But would have avoiding austerity saved Greece? It is all too easy to don a pair of rose-tinted glasses and argue that avoiding austerity would have kept growth in Greece steady and led to a sustainable debt position. But the counterfactual is not available, and it is as easy to argue that avoiding a more restrictive fiscal stance would have equally worried investors, who would be concerned about a lack of concrete steps towards debt sustainability. Eventually this would also prevent Greece from rolling over its public debt.

Restructuring the debt would also work only to a point. A significant amount of Greek debt was held by banks of other faltering eurozone countries, such as Italy and Spain, and debt relief could have brought over the edge those already fragile banking systems. Furthermore, a third of Greek public debt was held domestically, and as such a restructuring would also lead to demand-side drags on the economy.

Greece’s membership of the eurozone was critical in how the crisis escalated. If Greece still had control over its currency, it could simply devalue it, lightening the real burden of debt and bringing its current balance closer to equilibrium. Crucially, Greece also had no lender of last resort, as the ECB was bound by the Maastricht “No Bailout” clause. If the introduction of the euro were accompanied by a greater degree of federalism, this might not have been a problem, as there would be income transfers from the core of the eurozone through the action of automatic stabilisers.

Fearing the eurozone would unravel if nothing was done, the EU called on the IMF in order to provide for a first bailout of Greece in early 2010. While there were doubts from the IMF that the resulting arrangement was sustainable, it provided €30bn of financing, with other eurozone members providing a further €80bn.

As this happened in Greece, investors started to worry about the credit they were extending to other periphery countries. Their reluctance to extend financing translated into a rise in other countries’ borrowing costs. This was the so-called “sudden stop” that brought the eurozone to a halt. Portugal and Ireland soon needed bailouts of their own. Later, private sector involvement in subsequent bailouts made things even worse, as the losses forced on private bondholders increased the intensity of the capital flight.

At the core of the market panic was an apparent self-fulfilling crisis, with two internally consistent equilibriums. In the first “good” equilibrium, bondholders believe debt is sustainable, and therefore interest payments remain low, debt being then manageable. In a second “bad” equilibrium, bondholders start to doubt the sovereign’s ability to repay, and escalating rises in interest payments might mean debt is no longer sustainable. In traditional economies, a lender of last resort, the central bank, which is always willing to buy the sovereign’s debt, ensures the “good” equilibrium is the one to prevail. In the eurozone the “No Bailout” clause prevented this.

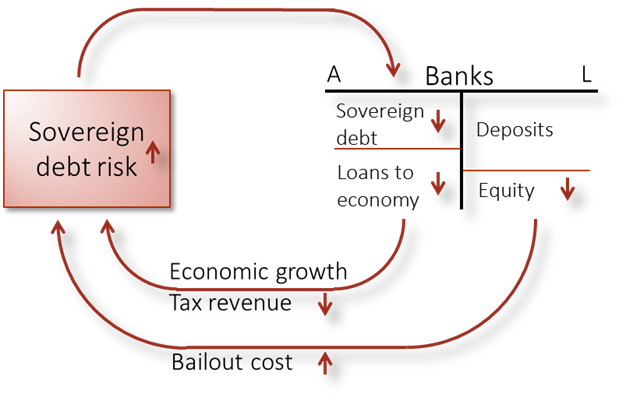

Equally relevant was a mechanism known as the “bank-sovereign doom loop”, which was crucial in the spread of the crisis to countries that had low public debt but large current account imbalances. Through this process, illustrated in the following diagram, failing banks have to be bailed out by the government, which leads to a deterioration of its fiscal position. As domestic banks tend to hold a disproportionate amount of home country bonds, this has a negative impact on their balance sheet. Gradually, both the situation of the country’s financial system and that of its sovereign become precarious. Concerningly, this issue has hardly been solved in the wake of the crisis, even though it could be solved by the simple introduction of a joint eurozone bond, as core countries complain of moral hazard problems.

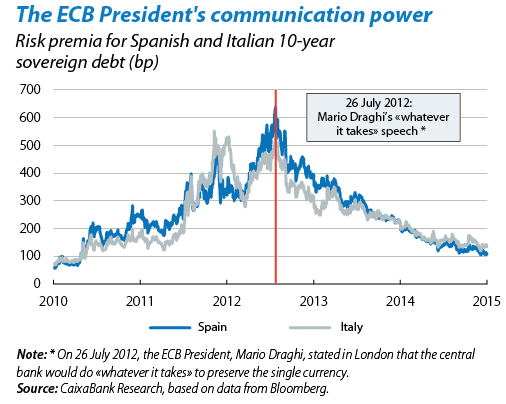

As the spreads of even supposedly safe countries like Belgium and France began to climb precipitously, Mario Draghi decided to take an unconventional turn in terms of policy. Pledging to do “whatever it takes to save the euro”, he announced the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program, which allowed the ECB to purchase government bonds of countries in distress. The program implied a very strict conditionality, with any countries joining the program being required to enact domestic reforms. This was done to allay concerns by core economies that peripheric countries would be allowed to ‘free-ride’ on the ECB, avoiding doing painful reforms. Even then, the program was legally challenged in the German constitutional court, as it was believed to breach the “No Bailout” clause. Thankfully, this was unsuccessful.

Ultimately, the true testament to the OMT’s success is that it has never been used. As soon as it was announced (its announcement coincided with the “whatever it takes” speech; see graph), spreads over the eurozone area started to drop. This ended up marking the beginning of the long road to recovery.

Nonetheless, the cleavages both exposed and exacerbated by the crisis seem to be here to stay, as Friedman ominously predicted more than two decades ago. Given the recent slowdown in eurozone growth, Draghi pushed the ECB towards restarting Quantitative Easing (QE), its large-scale program of liquidity injection into the bond market. The same core economies that long have run current account surpluses have opposed the move, citing not-so-new concerns on easy money being a deterrent of reform in southern economies.

The restart of the QE program also brings new problems, as the ECB already holds significant portions of debt of eurozone countries, and is required to hold less than 33% of each. Although increasing the limit is a possibility, it might put the ECB on the difficult position of being a majority debtholder of eurozone governments. This could be easily solved if countries like Germany and Netherlands, where the ECB is closest to its imposed limits due to their low amount of debt, used the fiscal space they have available to provide a much-needed stimulus for the eurozone. But they seem loth to do so. Only recently, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, Germany’s apparent chancellor-in-waiting, defended the country’s commitment to balanced budgets even in the face of an economic slowdown.

With Draghi now leaving his post, and Lagarde taking over, it is all too easy to hail this as a watershed moment where the eurozone finally casts off any lingering reminder of the crisis. But this would be a mistake. Europe’s economic dysfunction seems here to stay, and the shadow of the crisis will long hang over Europe.

This article was written in partnership with the Nova Investment Club.