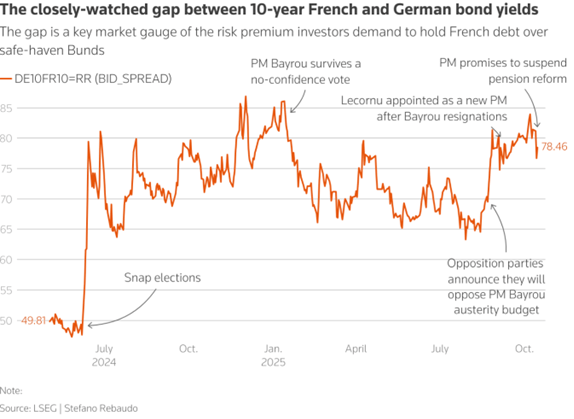

As we conclude 2025, the debate around the “AI bubble” has clearly shifted from a mere discussion of technological potential to a worried interrogation of financial sustainability. After three years of persistent AI investments following ChatGPT’s launch, the sector is now going through slowing growth expectations, skyrocketed capital costs, and doubts around future profitability.

Whether to the upside or downside, AI currently is and will be the main driver of the returns in the public equity market. But to allocate capital in the market, investors must feel confident that what is going on is not indeed a bubble burst.

What Defines a Bubble

A financial bubble happens when asset prices are substantially higher than their fundamental values. Investors go long (buy) when they believe an asset is undervalued, meaning it is priced under its fair price. But as prices keep rising, investors’ motivation changes, with the focus shifting from how much the asset is valued towards how much higher it can still go.

To determine whether the current AI cycle represents a true financial bubble, we can evaluate it against the phases defined by Charles Kindleberger and Hynan Minsky.

Displacement

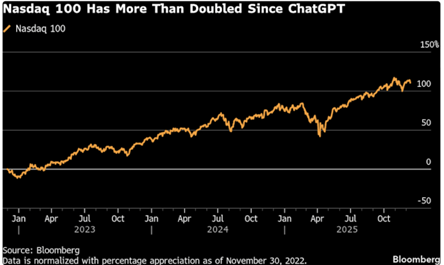

Everything starts from an innovation that fundamentally changes the perceived profit opportunities in a major sector. The launch of ChatGPT in late 2022 acted as the catalyst triggering a regime where technology was not simply considered a tool anymore, but rather a “New Era” of boundless productivity.

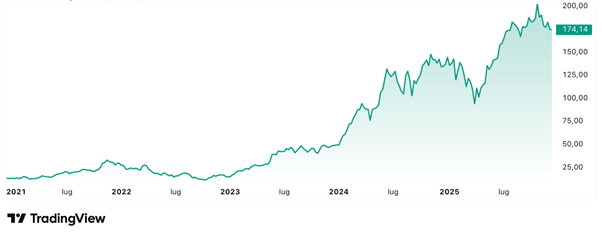

Over the last 5 years, NASDAQ-100 has delivered a total return of approximately 120.6%, representing a compound annual growth rate of 17.1%. An initial growth was driven by the post-pandemic digital shift, but the true catalyst was indeed the launch of ChatGPT.

Boom and Euphoria

Stability in this phase is officially destabilized. The sustained performance of AI leaders has been increasingly convincing lenders and regulators that the system was safe, leading to a weakening of credit discipline.

By 2025, the most profitable four technology companies at the global level are borrowing at rates that we haven’t seen so far since the telecom bubble to build infrastructure for demand that potentially may never arrive.

Only in 2025, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Meta invested over $400 billion on AI infrastructure, with current expectations according to Man Group of even $3 trillion over the next five years. Bain & Company estimated that to justify such CAPEX, such companies should generate $2 trillion in new AI revenue by 2030, literally a 100x increase from the current $20 billion baseline.

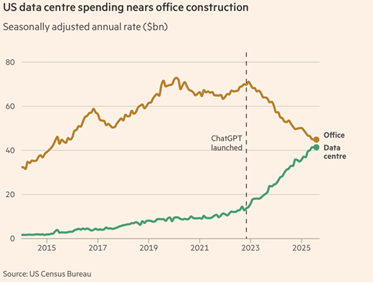

For example, since 2022, US investment has shifted away from typical office construction towards data centres, reflecting the rapid expansion in AI-driven infrastructure.

One of the biggest concerns about this is the change in strategy it deep down represents. The value of Big Tech was typically based on the ability to generate quick revenue growth at low costs, resulting in great free cash flows. However, their AI choices have now turned this model upside down.

This level of investment is extraordinary. At its peak, the 5G telecom buildout deployed about 70% of operating cash flows. AI infrastructure is going in the same direction. Hyperscalers are trying to power their own workloads, while AI developers are trying to train large language models (LLMs). Hence, big tech stocks have risen, but if computing supply is limited by insufficient power, then the AI bubble could deflate.

This bubble is indeed concentrated in such Magnificent Seven, which drive much of the S&P 500’s daily price moves. If their valuations fall, several portfolios will take a hint, even for people who think they are merely passively saving for retirement.

Panic

Analysts are keeping under control the Minsky Moment, that is the point where the system turns into a Ponzi scheme. A Ponzi scheme can be thought of as a scam scheme that promises a high return with little risk to new investors, relying on the word-of-mouth spreading about the big returns earned by early investors. Ultimately, if the flow of new investments slows down, it becomes impossible to pay out those supposed profits. That is when the Ponzi scheme collapses.

At this stage, borrowers cannot afford the repayment of their debt from current operations and must completely rely on rising asset prices to meet their obligations.

If we look at the 2025 AI cycle, signs of a Minsky Moment include:

- Accounting Illusions: The systemic extension of GPU depreciation schedules from 3-4 years to 6 years, which potentially masks a $176 billion earnings impairment “time bomb”.

- Credit Signals: Rising costs in Credit Default Swaps (CDS) for firms like Oracle (which hit a record 1.26% spread) suggest that lenders are beginning to reassess the risk of CapEx-heavy balance sheets.

- The Funding Gap: A projected $1.5 trillion shortfall in the capital needed for data center buildouts between 2025 and 2028, forcing a dangerous reliance on private credit and high-yield debt to keep the cycle alive.

This suggests that a “Panic” or “Profit-taking” phase could be triggered once a critical mass of investors realises that the forecasted 100x revenue growth will not materialise within the 2-3 year lifespan of the current hardware.

Nvidia As Barometer

Many look at Nvidia as the current market’s most reliable signal for whether the AI boom is grounded on reality or a fable of excess. We are talking about the main supplier of chips powering LLMs and data centres, hence its revenues are said to reflect actual AI spending. In other words, it is the heart of the AI infrastructure.

The stock has indeed become a proxy for the health of the overall AI ecosystem. When Nvidia’s stock price surges, it supports the confidence that AI is a productive investment, but when it falls, it creates doubts about whether capital is invested faster than what revenues justify.

No other company has benefited from AI spending than Nvidia. The stock, indeed, has surged alongside unprecedented GPU orders from cloud providers.

Key here is the chosen depreciation policy. Tech giants have lengthened their server lifespans on the books to six years. However, Nvidia’s products are made to be changed every year, making older chips obsolete and less energy-efficient.

For Nvidia, the next steps will rely on execution rather than hype. Markets are already watching closely to see whether hyperscalers will keep their capex as depreciation costs increase, whether demand will expand beyond a few dominant players, and whether AI revenue growth can cover the scale of infrastructure investments.

In particular, rising depreciation costs are pressuring buybacks and dividends, that is return for stockholders. In 2026, major actors as Meta and Microsoft are even expected to have negative free cash flows after accounting for shareholder returns.

If Nvidia will maintain a positive performance against those questions, it may actually fade bubble fears. Otherwise, its share price will reflect a market that changes expectations.

Conclusion

If on one hand fears of an upcoming bubble may be premature, the era of unquestioned enthusiasm is fading away in front of our eyes. Most analysts are not expecting a dramatic collapse as with the dot-com bust. Nowadays AI leaders are far bigger, more profitable, and better capitalised than their late ‘90s counterparts. According to experts, what might actually happen, instead, is a change within the AI trade, with investors favouring companies that have clear cash flow generations and scalability, against historically expensively valued names relying on flawless execution.

Sources:

Financial Times; Investopedia; Yahoo Finance; Bloomberg; Bain & Company; Business Insider; BBC; CNBC.

Rebecca Fratello

Writer