Since January 2025, more than 400,000 women have been leaving their jobs in the U.S., the steepest decline in over 40 years for mothers of young kids.

A female exodus that is dangerously erasing years of hard-won advances women made, particularly coming out of the pandemic, when flexible work policies enabled unprecedented labour participation rates.

Remote Work Trends And The Post-Covid Peak

On the wave of lockdowns, in May 2020 pandemics pushed almost 40% of employed Americans into working remotely. An undeniable jump, if we consider that just 3 years earlier only about 9-10% of workers would be reported working remotely. Later on, as offices reopened, that number fell, dropping to around 5.2% by September 2022 for those working remotely due to COVID.

However, remote work itself did not disappear. The pandemic left a mark in the labour market, as by early 2024 about 22.9% of U.S. employees were still teleworking. This shows how post-pandemic remote-hybrid work remained definitely more common than it was before, despite not reaching the emergency peak of 2020.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and USDOL/ETA

Flexibility, Remote Work, and Women’s Labour Force Participation

Historically, women have been overrepresented in roles more adaptable to remote work, such as education, administration, and knowledge-based services. Thus, it is not surprising that when flexible work options arose, many women would capitalise on them.

For both men and women, the possibility of working remotely decreased the likelihood of dropping out of work. But this effect was more visible for women. In fact, prime-age women’s labour force participation (ages 25-54) reached record levels in the U.S., hitting around 77-78% in 2023.

Source: The Hamilton Project, Brookings.

A Brookings analysis pointed out that since 2020 the group witnessing the fastest growth in labour force participation were those mothers with children under 5 years old. For most, indeed, remote and hybrid schedules created a bridge between work and family responsibilities, particularly also among highly educated or married women. Flexibility would not just retain workers, it actually unblocked participation from those groups previously precluded by rigid schedules.

But numbers speak loud: nowadays, something is changing.

Unaffordable Childcare and Caregiver Burnout

What is happening in front of our eyes is a clear childcare crisis. The stress and pressure to manage both career and childcare leave women overwhelmed and exhausted. In the U.S., many women struggle to find affordable childcare in a country with one of the highest costs in the world, often 30% or more of an average family’s income.

Source: Economic Policy Institute, via CNN.

Instead, countries such as Germany and Estonia have subsidised childcare, pushing down costs to near zero for many families. But many American mothers feel they have little choice but to quit their jobs. Similar story in the UK, where a recent survey has revealed that 43% of mothers revealed they had considered leaving their jobs due to childcare expenses.

Years of underinvestment and the end of expiration of pandemic-era subsidies are leaving American childcare supply in crisis. Women who have fought for their careers are now forced to drop out to preserve their mental health and family well-being.

Return-to-Office Mandates and Lost Flexibility

In January 2025, President Donald Trump ordered federal employees back in-person five days a week, despite many had remote work arrangements and some had even moved far away from their offices. Major private employers, such as Amazon and JPMorgan, followed the same wave.

It’s not a coincidence that women’s participation in the workforce is falling as flexibility disappears, says Julie Vogtman, senior director of job quality for the National Women’s Law Center.

Yet, return-to-office policies are not proven to make companies more productive. For instance, one 2024 study Van Dijcke, Gunsilius, and Wright of resumes at Microsoft, SpaceX, and Apple found that return-to-office policies led to an exodus of senior employees, which posed a potential threat to competitiveness of the larger firm. In other words, employers are losing talented workers, whose skills and institutional knowledge are difficult to replace. A talent drain that can even weaken the overall economy’s productivity and innovation.

To worsen things, women don’t feel respected in some workplaces, perceiving a clear cultural shift. Many have reported feeling less valued at work, with few diversity initiatives and a post-pandemic reversion to old norms.

It’s a pure storm of fading flexibility, harsher office demands and eroded support systems.

A McKinsey research suggests that women are even more likely to take on a lower-paying job if it implies benefits such as remote working and flexible schedules. If this trend increases, it will leave women disproportionately affected.

Furthermore, as women leave their jobs, the Trump administration is looking for ways to encourage women to get married and have more children, so as to slow down the country’s decline in birth rate.

Global Perspectives: Policies Matter

“The U.S. is the only advanced economy that’s had declining female labor force participation in the last 20 years, and a lot of that is because of lack of social safety net and caregiving supports” – Kate Bahn

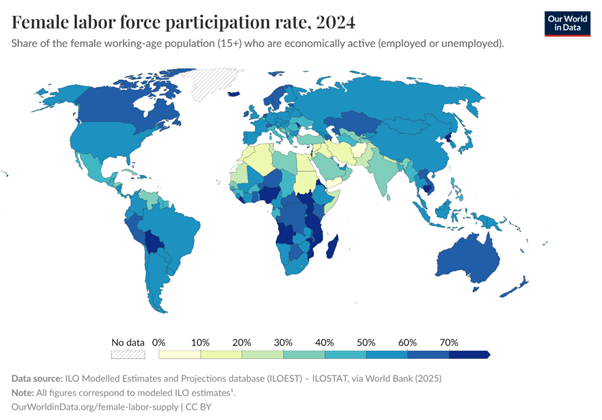

Globally, about half of all women participate in the labour force, with huge regional disparities persisting.

Source: Our World in Data (2025), ILO Estimates.

Deliberate policies have allowed women’s workforce participation to rise or held steady in many wealthy nations. Nordic countries like Iceland and Sweden lead in female employment, with gender gaps among the smallest in the world and a women’s participation rate of around 63-70%.

These countries differ from the U.S. as they heavily invest in affordable childcare, generous parental leave, and flexible schedules. Even the UK, Canada, and China have recently improved childcare subsidies or free preschool hours to push mothers to work. France and the Netherlands have high part-time options keeping women in the labour force, whereas Japan is pushing for “women economics” incentivising female employment.

On the other hand, countries that like the U.S. lack supportive policies see women pressed to choose between work and family, a choice that an emancipated society shouldn’t have.

Conclusion

Women leaving the workplace is not merely a personal or isolated decision. We are talking about a systematic problem depending on a complex interplay of societal norms, organisational practices and individual circumstances.

Factors such as work-life balance, career progression opportunities, social norms and expectations shape many women’s career decisions. Understanding the multifaceted nature of this trend is essential for designing effective strategies to retain and support women, ultimately benefitting the overall society and economy.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Time Magazine; Allwork.Space; The Washington Post; University of Kansas (The Care Board/CBS News); Brookings Institution; Federal Reserve (FEDS Notes); World Economic Forum; Institute for Women’s Policy Research; KPMG; The Economist; The Hamilton Project; The New York Times; McKinsey Global Institute; Our World in Data; Qureos; Return to Office and the Tenure Distribution, Van Dijcke, Gunsilius & Wright, arXiv (2024)

Rebecca Fratello

Writer