Global Infrastructure At Risk

We rarely think about it, but the modern economy is tethered to the stars. The invisible signals from Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites do far more than guide your Uber. They provide the precise timing stamps that synchronize stock market trades, manage power grids, and authenticate banking transactions.

This creates a terrifying fragility. If a conflict on Earth spills into space, it wouldn’t just be a military problem; it would be an economic cardiac arrest. Experts have long warned that attacking satellites is a double-edged sword because everyone, aggressor and defender alike, relies on the same physics to navigate, forecast weather, and communicate. We saw a preview of this chaos during the Russia-Ukraine war, where GPS jamming disrupted civilian flights and shipping across Europe. The reality is simple: the more we treat orbit as a battlefield, the more we risk the invisible infrastructure that keeps the world running.

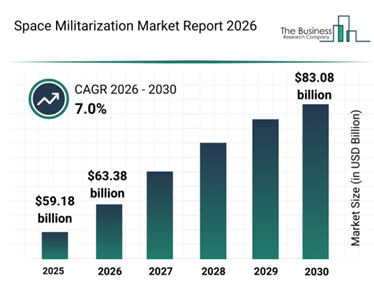

The Booming Market For Space Defense

Space is no longer just a frontier for science; it is a massive market for defense capital. In the last five years, global military spending on space has doubled, hitting $60 billion in 2024.

The forecast is clear: this is just the beginning. Analysts project the sector will grow to over $63 billion in 2026 and cross $83 billion by 2030.

This isn’t just about nations buying more hardware; it’s about fear. The United States Space Force alone requested nearly $40 billion for 2026, a 30% jump in a single year. But if you look closely at where that money is going, you’ll see a shift. Governments aren’t just building weapons to blow things up; they are desperately spending money to figure out how to keep their own lights on.

The Shift To ‘Soft’ Warfare

Military strategy in space is undergoing a quiet revolution known as “softwarization.”

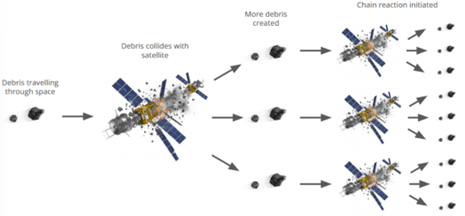

The logic is pragmatic. If you blow up a satellite with a missile (“hard kill”), you create a cloud of debris that could destroy your own satellites days later. It’s the orbital equivalent of setting off a grenade in a small room. Instead, nations are pivoting to “soft kill” tactics: jamming signals, blinding sensors with lasers, or hacking software. These methods can disable an enemy without turning low-Earth orbit into a graveyard.

Investment is increasingly focused on enhancing resilience. For example, new GPS satellites are being deployed with military-grade encryption (M-code) to better withstand jamming. Furthermore, satellites are now being designed with artificial intelligence to enable “self-healing” or the ability to reroute data automatically if a component is attacked. This trend has been described by one general as a “race to resilience.”

Debris: The Hidden Tax On Orbit

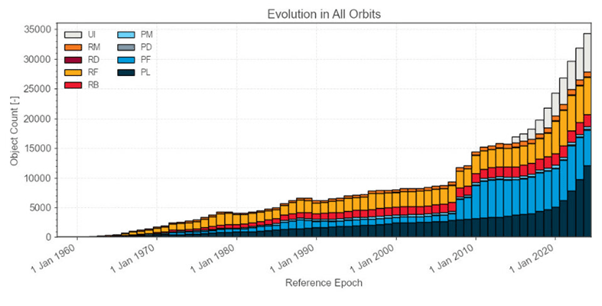

The biggest threat to the space economy isn’t a laser; it’s junk. Decades of launches and reckless anti-satellite tests have left Low Earth Orbit (LEO) cluttered with shrapnel.

Today, surveillance networks track about 35,000 objects in orbit. Here is the scary part: only about 9,000 are active satellites. The rest, over 26,000 pieces, is lethal garbage traveling at 17,000 miles per hour.

This creates a literal “congestion tax” for businesses. Satellite operators now have to burn precious fuel dodging debris, which shortens the satellite’s life and kills profit margins. Insurers are panicking, too, hiking premiums by 5–10% for missions in crowded orbits.

The nightmare scenario is the Kessler Syndrome: a chain reaction where one collision creates debris that causes two more collisions, eventually turning orbit into an unusable wasteland.

With China (2007) and Russia (2021) having already conducted tests that spewed thousands of fragments into space, the environmental cost of this “war” is already being paid by every commercial operator.

The Geopolitical Chessboard

Every major power is playing a different game:

- United States: The U.S. is betting on “safety in numbers.” Instead of relying on a few giant, vulnerable satellites (“Battlestar Galacticas”), the Space Force is launching swarms of smaller, cheaper satellites. If an enemy shoots one down, the network survives.

- China: Beijing sees space as the ultimate high ground. Since its 2007 anti-satellite test, China has built an arsenal of lasers and jammers while launching its own BeiDou navigation system to ensure it doesn’t need American GPS in a fight.

- Russia: Lacking the budget to match the U.S. dollar-for-dollar, Russia plays the role of the spoiler. It focuses on asymmetric threats, jamming signals (as seen in Ukraine) and threatening to target commercial satellites that help its enemies.

- Europe: Europe has woken up. Realizing it relies too heavily on others, the EU launched a “Space Strategy for Security and Defence” in 2023. They are building secure communication networks (IRIS²) and a “European Space Shield” to protect their assets.

Private Companies On The Frontline

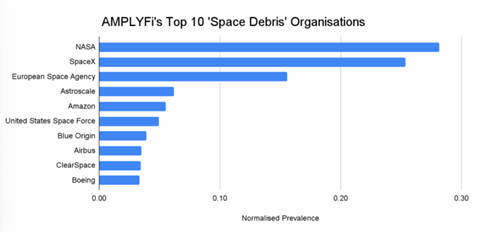

Perhaps the biggest change is who is involved. In the past, space war was for governments. Today, private companies like SpaceX (Starlink) and Maxar are on the front lines, providing communications and intelligence in active war zones like Ukraine.

This blurs the line dangerously. If a private satellite is helping an army, is it a legitimate military target? As corporations launch tens of thousands of new satellites, they aren’t just bystanders; they are active participants in a congested, contested domain.

Conclusion

Earth’s orbit is no longer a peaceful void. It is a busy, dangerous, and incredibly expensive industrial zone. The rush to militarize space risks destroying the very “commons” that our modern economy stands on. The next decade will decide whether we can manage this tension, or if we are hurtling toward a future where the skies above us are permanently closed for business.

Sources: Fortune Business Insights; Research and Markets; Payload Space; World Economic Forum (WEF); U.S. Space Force Financial Management; SatNews; NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center.

Rebecca Fratello

Writer